6 Minuten

Relative losses

Sound touches you, physically and emotionally, in ways that are specific to your own body, identity, and context. No one will ever listen to the same sound in the same way as anyone else. For one, the biomechanics of human hearing make it so that, even just with age, one’s hearing frequency range changes constantly throughout life. Some people are born deaf, and some, like me, become deaf later in their life. Some may experience a trauma that changes their experience of sound, or their hearing physiology may be suddenly altered due to a particular condition. All these cases are commonly understood as examples of hearing loss. But technically what happens is a shift or a narrowing in the frequency range that the ears can perceive. This of course affects the senses, but the senses adapt to the change in many ways and perception does not decrease, it just starts working in different ways than before.

If this physiological change is a loss, I wonder, it is a loss in respect to what? The answer is: in respect to normative hearing; those rules and standards that dictate what is “normal” to hear by exclusive means of the cochlear apparatus. The ISO 226:2023 also known as normal equal-loudness contour is a telling example. It defines a worldwide standard of how “human” perception of sound loudness works and claims this definition to be universal; in fact, it relies on experiments across an extremely narrow demographic: hearing people between 18 and 25 years old.

The question then becomes what exactly is lost when one’s perception of sound changes? Social context is a good lens to look through. In communicating, for example, some people may prefer adjustments to standard oral language (reading lips, slower and clearer speech) or may communicate with sign language. What makes these variations in communication to be understood as a loss is the fact that hearing people are generally neither ready nor familiar with these possibilities and therefore cannot – or refuse to – engage with those people. So, yes, due to my deafness, I suffer a loss, but it’s not a loss of perception, I perceive sound in other ways that are not available to hearing people. Rather, it is a loss of social engagement because hearing people find it hard to talk with me and me with them, or because some hearing people scream at me thinking that helps me understand them, or because my “loss” upsets them.

Western societies are designed for a speculative, universal body - one that is male, abled, hearing, and white – and therefore tend to exclude those who do not fit those criteria. One is disabled by society, not by their physical condition.

The knowledge of the other

I like to think that any attentive, focused perception of sound is a form of listening. It just may not happen through your ears but elsewhere in your body. And while you can, to some extent, perceptually filter out unwanted sounds, you cannot choose when to perceive them. Thus, sound is inherent to the body, and it participates in the body’s accumulation of knowledge. This leads us to a subject I have been invested in for the past two years: the embodied knowledge of sound enshrined in d/Deaf and hard-of-hearing bodies. What can be learned from it? How does it relate to technology and prosthetics? What does it tell us about sound?

I am myself a so-called late-deafened person, for, since my thirties, I have become increasingly deaf due to a generative condition. Driven by these questions, and because body, sound, and technology are the main media in my artistic practice, in 2022 I began a project to investigate, together with a group of fellow d/Deaf and hard of hearing people, our own experiences of sound. Entitled “I Am Your Body”, it is a long-term project that will manifest in several iterations over the next years. During its first iteration, the bulk of the project focused on collective research with the group and our findings became the core of my short film Niranthea and the performance Ex Silens. For several months, we had regular dialogues, collective brainstorming sessions, we made sound diaries and mind maps and discussed anything related to sound, deafness, and prosthetics: its technologies, the economy of it, the power dynamics, their affect and effects on the senses and social relationships.

Figure 2: Donnarumma in Ex Silens. The sonic prostheses are attached to the body by repurposing design techniques from cochlear implants.

Sonic prostheses

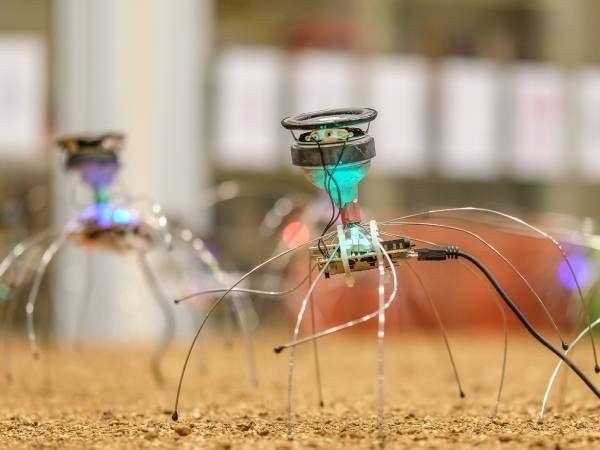

Leveraging this research, and in partnership with the Intelligent Instruments Lab (IIL) in Reykjavik, I created a set of sonic prostheses. These are wearable sound- and vibration-based devices that I perform with in Ex Silens. In their current form, at their core are basic, cheap acoustic transducers in the shape of bony constructs that, in the piece, I attach to my body and the bodies of the audience members as extra organs. What makes them interesting is their sound engine, a hybrid of analog and digital technologies combining physiological computing techniques - developed by myself for the XTH Sense; two machine learning libraries, Tolvera and Anguilla - developed by the team at IIL; and an algorithm for timbre-decomposition found in hearing prosthetics that I hijack via Flucoma. This system turns the otherwise humble and inert devices into alternative organs of sensing, as I like to call them. They can generate sound autonomously and respond to a performer’s muscular activity, which endows them with a peculiar aliveness. They can capture the heartbeat and other sounds of one’s body and transmit them via sonic and haptic waves to another body or multiple ones; they can be played as musical instruments leveraging vibrational feedback and contact microphones. d/Deaf, hard of hearing, and hearing people in the audience can all experience the sonic agency of the prostheses, each according to their sensory configurations. There is no “normal” way of listening to them.

Multitudes

This approach is meant, on the one hand, to turn inside out the medical understanding of hearing loss and deafness. It aims to open the meaning of listening, to embrace its infinite perceptual dimensions by mobilizing sound through different sensorial levels and several bodies at once. After all, one’s experience of sound is, at the same time, unique and (sensorially and socially) multiple. As we reflected at the onset of this text, you may not be able to fully describe your corporeal experience of sound to someone else. Yet, there are ways in which you can corporeally participate in the same sonic event that others are experiencing. If you are aware of the others’ particular modes of perception – that could be anything in the space across cochlear hearing and deafness - you may be able to explore your own experience of sound further; perhaps even to imagine theirs. On the other hand, the project approach to body technology is a statement: a prosthesis’ usefulness does not lie only in helping those who “lost” something to become “normal”; this is just a tired stereotype inherited from the times of eugenics. They, we, have not lost anything to start with and simply exist in a perceptual realm that interweaves with that of others, in an endlessly shifting constellation of sensorial modalities.

Acknowledgments

With thanks to PACT Zollverein in Essen and the Intelligent Instruments Lab at the Iceland University of Arts in Reykjavík for their support and critical exchange in the making of “Niranthea” and “Ex Silens”. “I Am Your Body” was funded by the Ministry of Culture and Science of the State of North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany, as a Medienkunstfellow.

Marco Donnarumma

Marco Donnarumma (DE) is an artist, performer, stage director, and theorist weaving together contemporary performance, new media art, and interactive computer music since the early 2000s. He manipulates bodies, creates choreographies, engineers machines, and composes sounds, thus combining disciplines, media, and technology into a oneiric, sensual, uncompromising aesthetics. He is internationally acknowledged for solo performances, stage productions, and installations that defy genres, and where the body becomes a morphing language to speak critically of ritual, power, and technology.

Article topics

Article translations are machine translated and proofread.

Artikel von Marco Donnarumma

Marco Donnarumma

Marco Donnarumma