12 Minuten

Devil’s Music is a performance piece about global media, local culture and individual interference. It developed in 1985 out of the confluence of my fascination with early Hip Hop DJs, a Cagean love of the splendor of radio, the introduction of the first affordable, portable samplers (Electro-Harmonix’s 16 Second Digital Delay and Super Replay), and a simple home-made “stuttering circuit” (inspired, perhaps, by my years as a student of Alvin Lucier.) In Devil’s Music the performer sweeps the radio dial in search of suitable material, which is sampled in snippets of one second or less. These are then looped, layered and de-tuned. The stuttering circuit “re-rhythmitizes” the samples by retriggering and reversing the loops in response to accents in the rhythm of the ongoing (but usually unheard) flow of signal out of the radio – in other words, the radio material you don’t hear is always governing the phrasing of the sounds you do hear, defeating the annoying periodicity of digital loops. The brevity of the samples is disguised by this constant shifting of the start and end points of the loop – a thrifty solution to the high cost of memory . All sounds are taken from transmissions occurring in the AM, FM, shortwave and scanner bands at the time of the performance; no samples are prepared in advance. The result is a jittery mix of shards of music, speech and radio noise -- sometimes phasing languidly, sometimes driving rhythmically, sometimes careening frantically -- a patchwork quilt stitched from scraps of local airwaves.

I have long assumed the radio to be the world’s cheapest, yet most powerful synthesizer: you can find any sound out there; the only question is, can you find the sound you want when you want it? Devil’s Music became my tool for playing this ethereal synthesizer, and the success of any given performance depended on the number, variety and character of local stations (New York City was easier than Ghent) – as well as, of course, dumb luck. A typical performance might start with a rhythmic loop sampled from a dance station; after a half-minute or so I ‘d add a wobbly chord lifted from an easy listening station, or a vocal phrase grabbed from a news bulletin, a taxi dispatcher or a cell phone conversation. The loops could be slowed down or sped up, and their pitch could be adjusted over a wide range -- either with potentiometers built into the boxes, or using a joystick I adapted to coordinate the detuning of two samplers (no piano-style keyboard was used for “playing” the samples.)

While the stuttering circuit drove these loops through their automatic variations, I’d scan the dial searching for the next sample. At first I worked with one 16 Second Delay and a single Super Replay, and was limited accordingly to layering two loops at any time. Later I invested in a second Replay, and the additional voice increased the richness of the mix. Even then, however, I preferred to keep the texture clear enough that the individual samples could be distinguished, and was never tempted to add more channels or additional processing.

The piece moves by pseudo-Baroque suspension and resolution, as samples are replaced one after another, occasionally punctuated with abrupt multi-voice changes or sudden channel mutes. The introduction of the second Super Replay gave me the option of occasionally “re-sampling” and sustaining indefinitely the first two channels of looping textures, thereby freeing up those other circuits for new samples. Some material would be chosen for the sake of sonic continuity, while at other times I would string together a haphazard narrative from spoke words scattered across the dial. The blessing and curse of working in certain foreign countries was the ability to treat speech as “pure sound”; it might be gibberish to me, but I remained dimly aware that it might actually mean something to the audience (after one performance I was told that I had unknowingly transformed a corrupt Swedish politician’s economic announcement into the statement “my boots are smelly”).

(left) Performance in “STEIM Symposium on Interactive Music” at De IJsbreker, Amsterdam, 1985 / (right) Live performance somewhere in France, 1985-87.

Devil’s Music was made for the modern wandering minstrel: every performance was different, topical, extracted from the local airwaves. After a disorderly premiere at the Anti Club in Los Angeles in 1985, I presented the piece some 100 times across North America and Europe over the next three years. During each concert there came a transforming moment when the audience realized what was happening: a word from a local newscaster or the score from that day’s football match hinted that this was not off-the-rack electronic noise, but was made-to-measure out of the here-and-now, just for us.

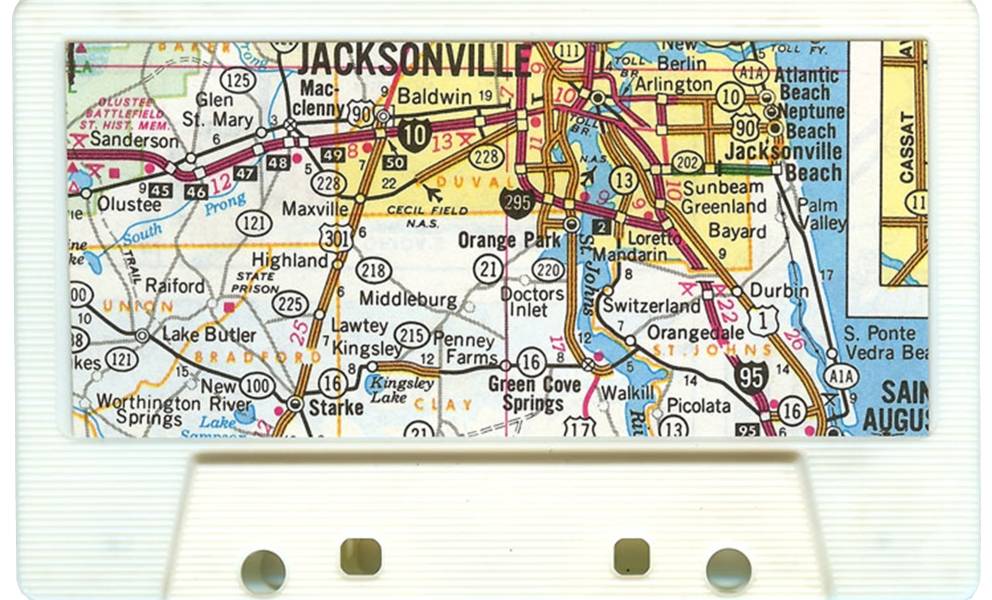

Devil’s Music got around. Live performances from Berlin, Chicago and New York were released on Slowscan, Tellus and Trace Elements cassettes. Excerpts from a 7-city tour that stretched from New York to Budapest to Bern were compiled into a limited-edition 50-minute cassette tape for Banned Production in 1987, titled Real Landscape (with a nod to Imaginary Landscape No. 4, John Cage’s infamous 1951 composition for 12 radios). Each Banned cassette was lovingly hand-packaged in a road map conned out of offices of the American Automobile Association by the label’s producer, AMK.

Real Landscape, Packaging, booklet and cassette. Released by Banned Production, 1988.

In 1986 I released an LP of Devil’s Music on Trace Elements Records. Rather than representing a typical concert performance, I chose to focus two particular regions of the piece’s palette: the A-side was an “encyclopedia of break” -- several takes that sampled New York’s best dance music stations, with an overlay of vocals grabbed from advertisements; the B-side mashed classical and easy-listening stations into a into a Reich-meets-shattered-Glass lounge music. Aware of the semi-clandestine market in “break beat” discs that collected hot rhythmic grooves from other records, I hoped that DJs everywhere would buy one copy of Devil’s Music for jolts to the dance floor, and another as a gift for their Mantovani-loving grandparents or their Minimalist moms and dads. These hopes were misplaced at the time, but by the early 90s I was hearing rumors that the LP was being played in House clubs in Berlin and changing hands at record conventions for considerably more than the original list price. I’ve yet to see anyone dance to it, but one day….who knows?

As recordings of specific performances, the cassettes and the LP constitute sonic snapshots of places and moments – befuddled playlists at play. As with photo albums or vintage TV commercials seen on You Tube, the passage of time not only adds a nostalgic haze but also imbues both the content (the voices and music of another era) and the method (the earliest instances of the sampling technology that is now ubiquitous) with new meaning.

The title, Devil’s Music, was a nod to the rising paranoia of the Christian right, its pre-occupation with obscene lyrics and masked satanic messages in Pop records. The herky-jerky rhythm of Devil’s Music seemed to suggest a dance of demonic possession, while the stew of backwards samples could easily have camouflaged the subliminal messages and evil incantations that were rumored to lurk in every distorted vocal line since the Kingsmen’s Louie Louie. The album cover image was taken from a Con Edison “High Voltage” sign I found in the street, elegantly adapted by a designer friend, Amy Bernstein. I thought the man-struck-by-lightning logo neatly conveyed the St.-Vitus’s-Dance-quality of the music. (In 1989 the same image appeared, in an almost identical layout, on an EP by Fidelity Jones on the Dischord label; and when Wired magazine started up a few years later it used the same icon to mark its reviews section. But it would be folly to accuse another of plagiarizing one’s own plagiarism.)

Even after dropping Devil’s Music from my concert repertoire I retained a great love of the soundscape of radio, especially in its mistuned, noisy and clandestine states. I carried a small multi-band radio with me as I traveled, and recorded electromagnetic chatter wherever I went. In 1988 I mined these cassettes to produce one of my few tape compositions, The Spark Heard ‘Round The World. Commissioned by New Radio and Performing Arts, the piece sequences fragments of conversations from cell phones, ship-to-shore radios, CBs, cab dispatchers, and fire and police communication; under this I layered highlights from my collection of those noises and whistles that shortwave yields so effortlessly. The stuttering rhythm of Devil’s Music is absent here, the insistent looping replaced by a disjointed found narrative embedded in a more immersive, laid-back radio ear fest.

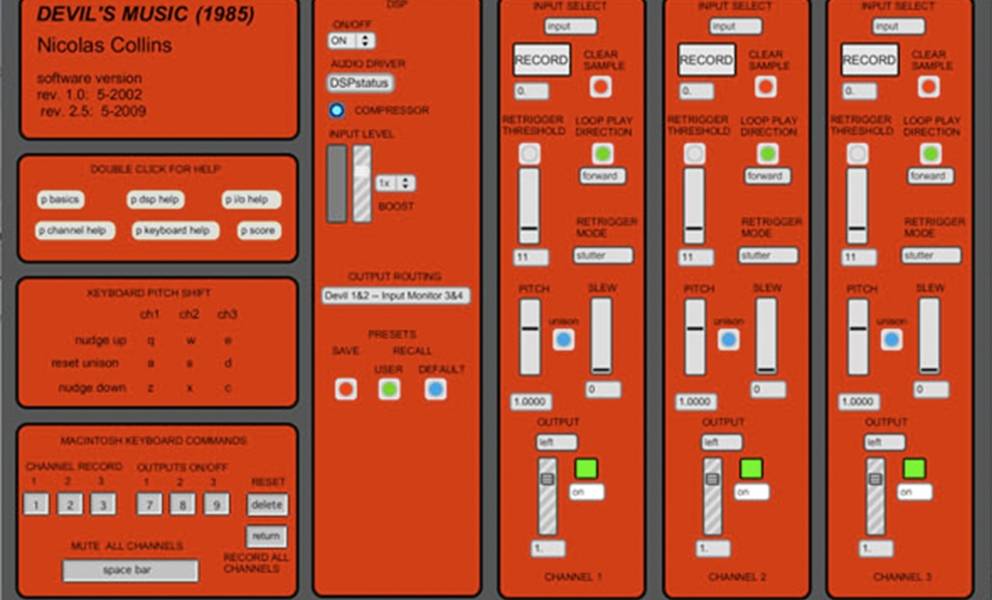

In 2002 Chicago-based producer John Corbett invited me to revive Devil’s Music as an antidote to the “Laptronica” that had come to dominate the electronic music scene. My original circuitry lay corroding in an attic in New England, and I thought it was time to trust the piece to fresh hands and ears, so I set about cloning the hardware in software. For me what had made Devil’s Music a composition, rather than just an instrument or collection of effect boxes, were the limitations intrinsic to the original hardware. Instead of imposing an external musical form, I had let the idiosyncrasies of the circuits determine the microstructure of the piece (a habit I shared with David Tudor and my peers in his “Composers Inside Electronics” ensemble). The automatic re-triggering in response to the streaming radio defined the rhythmic essence of the work; the specific patterns might change as that stream shifted from Techno to Tchaikovsky to Tatum, but the phrasing retained a consistent, identifiable character. Likewise, the short sample time, limited range of pitch transposition, small number of voices, and lack of additional effects all served to delineate the boundaries of the piece very clearly.

So I strove to “hardware-ize” my software. I tried to reproduce the quirks and limitations of the original circuits as faithfully as possible, rather than succumbing to the typical programmer’s temptation to “improve” upon them: numbers in a program can always be made larger or smaller, but physical sliders and knobs have limits past which they will not move; accurate mimicry respects weaknesses and boundaries as well as strengths. I also sought out peculiarities in the programming language that could color my code in the same way that my circuitry was constrained by physics (one innovation arising from such a software idiosyncrasy causes a sampled phrase to reverse with a pitch slurp reminiscent of back-and-forth turntable scratching -- given the DJ-manqué roots of Devil’s Music I thought this a not inappropriate addition).

I wrote the program in Max/MSP and emailed it to ten Chicago DJs, computer musicians, improvisers and re-mixers . It could run on any Macintosh with no additional hardware besides a radio and a pair of headphones. I kept the score to a minimum: you can do anything as long as you only use this program and a radio. The premiere at The Empty Bottle in May 2002 consisted of two hours of overlapping solo and duo sets of 5-10 minutes each. Each set managed to sound simultaneously like my original piece and like the artist’s own music, which was exactly what I had hoped for.

I revised the software several times over the next few years, beta-testing it in concerts with Sicilian Techno DJs at the Prix Italia in Palermo, with Berlin Electronica musicians at the Maerz Musik festival, with some former students at the River-to-River festival in New York City, at a workshop in “Diskless Jockeying” that I gave in Glasgow, and in several solo concerts. The program has begun to spread beyond my direct contacts, so I occasionally hear of far-flung performances that have taken place without any effort on my behalf. For me the most significant software-specific attribute of the new Devil’s Music is this ability to distribute the program widely, at no cost, so that the piece is no longer dependent on my personal hardware, listening taste, or performance style. In 2008 EM Records in Japan re-issued the 1986 Trace Elements recording as part of a gatefold package, accompanied by a second LP containing the Real Landscape cassette release; the double CD version of this project also included a previously un-released radio collage commissioned by New Radio and Performing Arts in 1988, the software for self-performance of Devil’s Music, and a video of me performing Devil’s Music in Birmingham, Alabama, in 1987. In 2015, to mark the 35th anniversary of the piece, I updated the software for live performance.

In 2001 Philip Sherburne called Devil’s Music “an early template for Techno,” but despite the presence of the rhythms, sounds and sampling techniques of Hip Hop, the record didn’t cross over into the dance music scene when it came out in 1986. It was too early a template for a genre that was still years away. In 1986, as Robert Poss once said, the piece sounded like “an intro that never settles into a groove”. Instead of settling, Devil’s Music remains unsettled and, as with seasickness, the lack of a stable horizon can induce a queasiness that only dry land and a firm beat can dispel.

At the time, live sampling and the use of computers and radios on stage were limited to the lunatic fringe, but today the technology, techniques and aesthetics of Devil’s Music are part of the common culture of the DJ and Pop-oriented electronic musician. Hearing it after so many years, performed by others, makes me realize that Devil’s Music is the closest I’ve come to writing a “standard” -- something that can be covered by a broad range of performers and enjoyed by an equally diverse group of listeners. It may or may not be danceable, but Devil’s Music would appear to have legs.

Nicolas Collins

Born and raised in New York, Nicolas Collins studied with Alvin Lucier, worked for several years as a member of David Tudor's ensemble "Composers Inside Electronics" and has been an active member of the worldwide improvised music community since the 1980s. He spent the 1990s in Europe, where he was artistic director of STEIM (Amsterdam) and guest composer of the DAAD Artists-in-Berlin Program. He is a professor in the Department of Sound at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and a research fellow at the Orpheus Institute (Ghent). An early adopter of microcomputers for live performance, Collins also uses homemade electronic circuitry and traditional acoustic instruments. His book "Handmade Electronic Music - The Art of Hardware Hacking" (Routledge), now in its third edition, has influenced electronic music worldwide.

Article topics

Article translations are machine translated and proofread.

Artikel von Nicolas Collins

Nicolas Collins

Nicolas Collins