10 Minuten

People walk on the street. They walk past you, all at their own pace. They walk past you, get louder, get quieter again, spatially distributed. The pounding continues further away, at different distances and at different steady tempos ... The acoustic pounding of pedestrian traffic lights as you cross the road, one pounding pulse after another.

We are used to hearing pulsation overlays and moving within them. Tutti pulsations, i.e. joint, simultaneous pulsations, are something we are hardly familiar with in ambient sounds. A "tutti walk", for example in the military, is hardly interesting in terms of sound, perhaps even sociologically. The sonority of the different pulses and the spatial movement within them have fascinated me for a long time and represent a central theme of my musical work. It is the superimposition of different tempos and their compositional effects that are so interesting to me.

Realization

Technique

In order to realize tempopolyphonic music, i.e. music in which different tempos happen simultaneously, I use the technical aid of click tracks. There is usually a separate click track as an audio file for each musician. All these audio files are started simultaneously and played to the individual musicians via headphones. I usually use in-ear headphones for this. This has the great advantage that the sound of the click is less perceptible on the outside, but also makes it harder for the musician to hear the sound being played. The bone sound headphones should be mentioned in this context. These transmit the sound to the inner ear via the cheekbones and the skull bone, leaving the ear free for listening. I haven't tested these enough yet. In a first test, this type of headphones seemed very effective to me.

All audio files are started simultaneously in the music software and each signal is sent to the headphones via a different channel of the audio interface.

If, for example, MP3 players are used instead of this technique, whereby a different click file is played on each player and all players are started together at the same time, it is important to remember that each player has a slightly different playback speed!

This means that a composed tutti of all pulses is no longer possible after a few minutes due to the divergence in speed!

The click

I have found that click signals, such as the often used clave sounds, resonate in quiet passages and can therefore be heard by the listener. I use sine waves of different pitches, which are multiplied by an exponentially decreasing curve (1 to 1/100) of two different lengths. The longer ones for the 1, the shorter ones for the remaining beats of the bar. The bar number is also announced every 5 bars.

The notation

Due to the different tempos, it is important to bear in mind that each player is playing in a different time signature with a different number of bars. Let's assume that instrument 1 plays ♩ = 60, the second instrument ♩ = 120. Both play in 4/4 time. In this simple example, at second 12, the first instrument would be in bar 3, the second instrument in bar 6.

In order to represent these tempo relationships, I first create the score, in which I then write. In doing so, I make dots in the top stave of the line at which the crotchets are played in the respective tempo.

Let's assume instrument 1 plays tempo ♩ = 60, instrument 2 ♩ = 73, instrument 3 ♩ =78.

Let's say 1 second in the score corresponds to the length of 1.5 cm. So the distance between the quarter notes for instrument 1 would be 1.5*60/60, i.e. 1.5 cm, for instrument 2 1.5*60/73, i.e. approx. 1.23288 cm and for instrument 3 1.5*60/78 1.15385 cm.

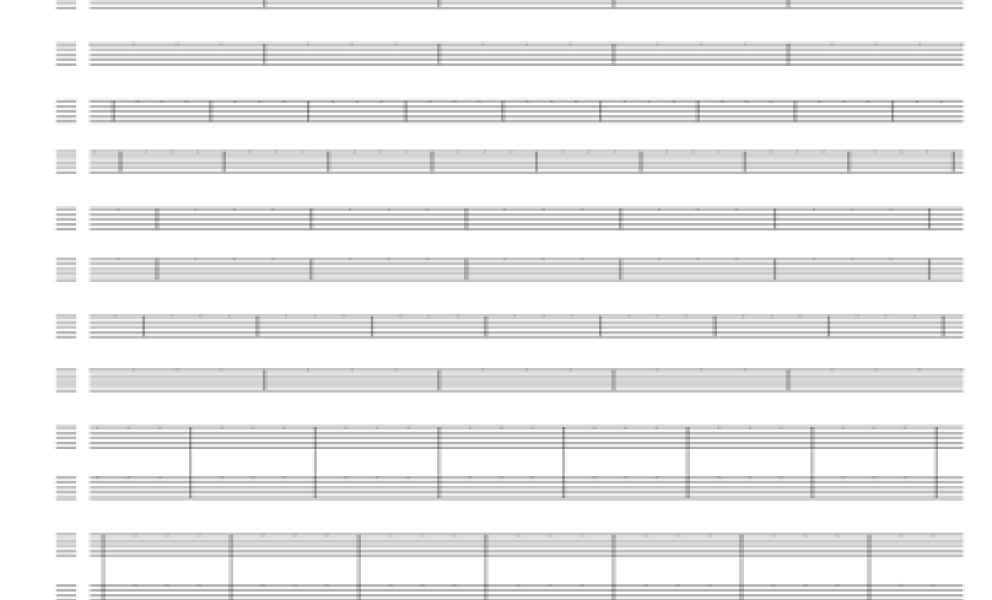

This results in what I call tempo nets. As an example, here is a score page from my ensemble piece "beneden".

This type of notation is a type of space notation. It is also the case that everything that is under each other also sounds at the same time. If the instrumentation and the number of different tempi increase, you reach the limits of legibility:

In my mass, a choir of around 60 voices sings the Gloria. Since the exact synchronicity of the voices and tempos was not important to me in this piece, I created an audio track for each voice, which was started and played simultaneously on mp3 players by the respective singer. This track contained a melody that the singers sang along to - each melody of the individual voices in a different tempo.

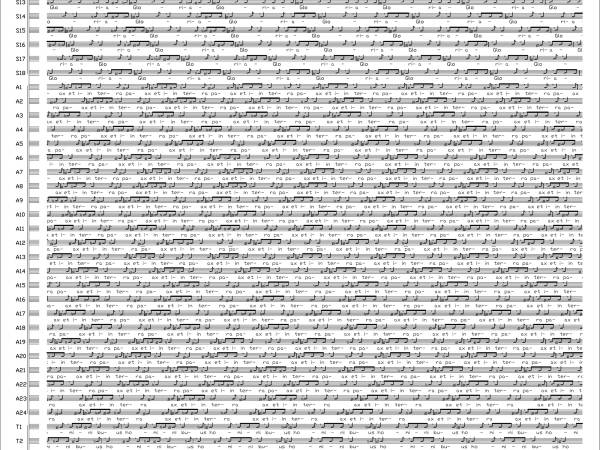

I created a tempopolyphone score of the Gloria for the choirmaster. I created the score page in a graphics program using the system described above. With classical notation programs such as Sibelius or Finale, tempo-polyphonic scores are almost impossible or only possible with an immense amount of work and also do not produce exact precision.

This page was created:

As you can see, the result is what I consider to be an impressive page of notation, but its legibility has its limits. It is impossible for a musical director to say exactly whether each voice has played exactly right. All you hear is more textural sound. Paradoxically, therefore, a precisely accurate notation of tempo polyphony leads to an image of notes that can no longer be grasped exactly in terms of sound. One can only orient oneself approximately.

Together with the conductor and composer Jaime Wolfson, I have developed a system for another piece on how such dense tempo-polyphonic interweavings can be represented in a notation:

In my piece "Saitenraum II" for 60 strings in three connected rooms (each instrument plays at its own tempo), there is a passage in which the notes of a melody change in quarter-tone steps until all the notes reach the same pitch in different octaves. The pitch changes take place in a similar time period (1 - 3"). We opted for the solution of writing only one part in the score; only the bar lines with the quarter notes are given for the other parts. This was the best way for the conductor to read the essentials from the score. However, the individual parts were fully notated.

Construction

The text "Wie die Zeit vergeht" by Karlheinz Stockhausen was formative for my tempopolyphone work. In this text, he places two musical parameters, which had previously been regarded as separate, on one axis: rhythm and pitch. He starts from the premise that a pulse, e.g. rectangular pulsation, up to approx. 16 Hz is perceived as a pulse, i.e. as rhythm. If this pulse is accelerated, a pitch is created. Stockhausen concludes from this that rhythm and pitch can be thought of on the same axis.

For this reason, interval proportions can be transferred to rhythm proportions. For him, the interval proportions of 2:1, i.e. the octave, can be transferred to the rhythm: a half note to a quarter note, - an eighth note to a sixteenth note is a "continuous octave".

From this consideration, he created his groundbreaking work "Gruppen für drei Orchester". He derived rhythm and pitch constellations from a symmetrical all-interval series according to the principle mentioned above.

This idea of seeing pitches and durations on the same axis and, above all, reconceptualizing tempo relations has had a lasting influence on me.

In one of my first tempo-polyphonic works, "Puls 3" for automaton piano (automaton by Winfried Ritsch), I had each pitch of the piano repeated at a different tempo at one point in the piece. I based the design of the individual tempi on Stockhausen's ideas. Since in a well-tempered system only the octave is pure and the 12 semitone steps are understood to be of equal size and therefore mathematically have the 12√2 as a factor, I initially created the tempi of my piece according to the following principle: the tempo of the repeating c with the 12th root of 2 gives the tempo of the repeating c sharp, this multiplied by the same root gives the tempo of the repeating d and so on.

The tempo of subcontra a =25, the tempo of subcontra b= 25*12√2= 26.49 and so on.

This resulted in the following problem: since each octave gives twice the tempo, this principle gives me the following tempo for c5: ♩ = approx. 3805, which was of course completely unusable. If I only apply the principle to two octaves, the highest tempo is four times as fast as the lowest and results in the following sound structure: (starting note small c with tempo ♩ = 60, highest note c2 with ♩ = 240)

I was not satisfied with the sound result. The pulsations in relation to each other seemed too even, too static and, after a while, tediously boring - in short, I found the sound result unsatisfactory.

In my further search for a suitable tonal possibility, I came across the ratios of prime numbers, i.e. natural numbers that are only divisible by themselves or 1.

I assigned a prime number to each individual tempo.

I tried to keep the factor smallest tempo to largest tempo as in the previous example (i.e. 4), and came up with the following possibility: smallest prime number 41, ascending to largest prime number 163.

This gives me the following tempi:

Tempi of small repeating c: 60*41/41; of small c sharp 60*43/41, of small repeating d 60*47/41 and so on.

This results in the following tempo-polyphonic texture:

In this example, I have used the prime numbers in a sequence. There are countless other possibilities. If I compare the "well-tempered tempo scale" with the "prime number tempo scale", the latter sounds much livelier and more exciting to me. The relationships between the individual pulsations seem more variable, not static, the mesh seems more alive.

I can only speculate about the mathematical reason for this: The order of the prime numbers cannot be described by a function. Perhaps it is precisely this mathematical elusiveness that makes the sound tangible and interesting.

And there is another point that fascinates me: if I use prime number ratios for the individual tempi, the following aspect comes to light:

With 24 different tempi (as in our example), there are always different temporal relationships between the pulsations. Mathematically, these relationships are only repeated after the prime number P1*P2*P3 and so on. units. In other words: In our example with the smallest prime number of 41 and the largest of 163, the relationships of all pulsations to each other only repeat after 464362553 units! In other words, you never hear the same relationships to each other throughout the piece!

There are always condensations and dispersions of the pulsations, but these are always in a different constellation to each other.

Since my earliest pieces, I have always used prime number ratios to create the individual tempi.

Possibilities

The overlapping of tempo layers described above and the compositional work with them have been opening up new possibilities for me for years.

Chiseling sounds, the compositional design of textural and structural sounds through precisely constructed accelerandi and riterandi, which merge into tutti pulsations, are immanent design principles of my compositions. New possibilities also arise:

In my piece "Saitenraum 1 und 2", I distributed the tempopolyphonic structures across different rooms that could be entered by the audience. Phase shifts occur between the individual rooms, which gradually merge into tempopolyphonic meshes. Minimal rhythmic shifts can be experienced acoustically by the recipient themselves. Furthermore, the click technique allows amateur musicians to be involved in the interpretation of the piece. For me, this is a great opportunity, as new music is too often created, interpreted and perceived exclusively in an expert environment.

In my pieces "Puls 4" for 35 tubes (for the opening of Musikprotokoll 2010, written for the molecular organ developed by Constantin Luser, consisting of 35 brass instruments), amateur musicians from various brass formations in Graz played the piece. They usually only had to play on the beat of the respective click. However, I composed these beats in relation to each other so that their overlapping formed complex sound fabrics.

In my piece "little beauty" for variable instrumentation between 40 and 80 wind instruments, which I premiered at the New Music Festival Dublin and the Wittener Tage für neue Kammermusik in 2024, I worked with a more open form: I only gave the individual musicians possible pitches, as well as rhythmic patterns (each instrument at a different tempo), which changed at different times in the individual parts. The performers were free to choose from the range of pitches. This freer arrangement was well received by the musicians, allowed them a more open musical arrangement and motivated me to continue working with it.

Together with the choreographer and animation filmmaker Paul Wenninger, I am currently working on making physical and cinematic movements as well as acoustic sequences and shifts tangible.

In another project, I am trying to construct the ambient sounds of an urban environment as well as possible through a temporal compositional plan using acoustic cues, thereby creating a distorted, alienated reality.

In many of these works, the awareness of the sound that surrounds us and that we constantly produce is an important concern for me.

Working with clicks, working with this technique, is unfortunately all too often perceived as unmusical - as "anti-musical". At one of my lectures, this technique was even described as the downfall of musicality, yet this special implementation creates a multitude of new, exciting musical possibilities.

And: weren't electronic music and many other musical innovations once also seen as the downfall of music?

Peter Jakober

Peter Jakober was born in Austria in 1977 and lives in Vienna. From 1998 to 2006, he studied composition with Georg Friedrich Haas and Gerd Kühr. His works have been performed at numerous renowned festivals. His piece "Saitenraum 2" for 60 strings opened Wien Modern 2023 in all three halls of the Wiener Konzerthaus simultaneously. The music theater Populus was awarded the Johann Joseph Fux Opera Composition Prize in 2018. Music for performance. Jakober received the Erste Bank Composition Prize 2015 and was a fellow of the Akademie Schloss Solitude.

Article topics

Article translations are machine translated and proofread.

Artikel von Peter Jakober

Peter Jakober

Peter Jakober