9 Minuten

Introduction

Western Common notation continues to serve music of the past very well. It's suitability for modern music has been challenged over the last 120 years, as compositional ideas moved away from the 12-tone tempered scale, and electronic sound synthesis offered the potential to explode our sonic imaginations. Learning Western common practice notation is time-consuming, with some people starting from a young age, refining their ability over decades. It is also expensive for many, and only available to some. After years of study, reading music notation becomes embedded in the physiology of performing an instrument, a kinaesthetic connection between movement, listening, and seeing. It can shape the understanding of an instrument, of what is possible, and what is best, or at least, most common and useful in terms of technique. In my own experience, it has been difficult to ‘unlearn’ this embodied effect - unsurprisingly. One of the effects is the connection between the operation of a musical instrument to tonality, the organizational system supported by this notation. It facilitates the harmonic structures that inform melody, chords, and their progression that in my case, became embedded in my literal physical being as a flute player. This shaped my improvisations in very particular ways, and despite trying to break away from these organizational structures to be able to improvise truly freely, I am not sure it will ever be possible.

Notation and the value of musicianship for all

Despite this, I believe reading music together is a valuable part of many musicians' experience, and an expression of musicianship beyond the individual performer's persona. Music notation provides a recognizable, decipherable code as a way to navigate and share complex musical ideas with other musicians. It provides a way of making sense of singular parts in the whole of a composer’s design. It enables the collaborative reward of taking part in a pre-designed sonic trajectory. Of course, performers all navigate this music ‘code’ slightly differently, shaped by the technique and color of our instruments, our favorite recordings or performances of established works, our teachers, abilities, emotions, ideals, and context. The code itself changes, as different cultures have music systems that may draw focus onto different elements of music performance and invention. But what they all do have in common, is capture musicianship - shaped by a large number of elements - but positioned at the heart of it is playing music together. As electronic tools for music-making evolve, so does our musicianship. This includes an evolving digital musicianship (Hugill, 2018) which brings with it many possibilities yet to be explored.

What if we flip the traditional nature of notations, and introduce notation systems that can be learned instantly, without the years of study? Notations that could move focus away from the melody and pulse so strongly represented in common practice notations, and toward richer representations of dynamics, ensemble communication, texture, and structure, enabling new sonic worlds released from centuries of claviocentricsm (Diduck, 2012, p.34). For experienced musicians, this notation would draw on pre-existing musicianship, assuming a level of skill and control of the instrument. This musicianship could be from any musical style– art music, jazz, pop, folk, free improvisation, electronic music – learned through performance and experience. Musicianship unfolds across different styles and genres, defining the key elements of the musical experience - what to listen for, the nuance of tunings, of playing in time, or out of time, together. Importantly, it could be designed to enable those excluded from reading traditional notations – such as those with a different range of sight, hearing, or physical ability. Electronic, folk, improvising, and pop musicians could form ensembles together, alongside many different instruments and styles. Digital tools enable us to embed audio-visual elements into scores, such as a wide range of colors, motion, sound, and computing that can control external devices such as robots. This is already happening – an example is Jess +, a robot arm functioning as an intelligent digital score system for ensembles with differently abled musicians. Jess+ and similar systems engage intelligent computation systems as co-creators, offering differing degrees of felt cooperation, presence, and autonomy (Vear, DigiScore).

Graphic notation

Graphic notation has been consistently engaged by composers and musicians throughout music history, often as a halfway place between composing and improvising, creating space for performer contributions and providing a useful starting point for the possibilities of the future of notation. Similarly, we can build on charts and tablatures more often used by folk, pop, and jazz musicians. These often signal the harmonic foundations of works, and leave the performers to provide the rest – but can also provide ways to signal other information. In addition, many new notation systems have been devised and proposed (systems such as Bilinear notation, global notation, and Dodeka come to mind - see the Chromatone Centre for some) yet the failure to adopt them points to their limitations and aims as ‘ one size fits all’ or a retrospective position on music tied up in tonality and acoustic instruments. I find it interesting and frustrating in equal measure that notations remain very style-specific, driven by the expectations and historical prefixes of the genre. This is despite significant development and impacts of other technologies, such as the Digital Audio Workstation, which have been developed and adopted for universal use – though hegemony and accessibility for differently abled people remain a challenge (see Terren, n.d), and these developments focus on individuals, rather than collaboration.

As a composer and performer myself, I have been trying to create music notations that can be read by musicians from any instrument and stylistic background. This journey began with the desire to notate electronic music in a way that would enable electronic musicians to be part of chamber music performances. I also curated historic chamber music featuring electronic parts for my ensemble, Decibel. This led to the commission of new works for chamber music with electronics, and I started to see a wide range of approaches toward notating electronic instruments and sounds, in addition to the existing historical range of efforts. There is a plethora of approaches, bespoke to evolving technologies and musical ideas – but what they all have in common is a desire to organize and coordinate electronic and acoustic musicians. Outside of that depends very much on the composer’s intentions, whether or not the score intends to describe, or prescribe the activity of electronic sounds, and how interactive these sounds may be. Early pioneers of notation for electronic music can teach us a lot about the role of writing for electronics – Percy Grainger’s ‘Free Music’ works for groups of theremins from the 1930s use a notation that at once instructs the performer and describes the sound. John Cage notated tape assembly in ‘Williams Mix’ in 1952, and Daphne Oram drew shapes to control electronic sounds in the 1950s using her Oramics system. Whilst there are many other examples, the point here is that the parameters for notation don’t need to be determined by anyone other than the creators of it, and those they wish to perform it.

How I got notation to work for me

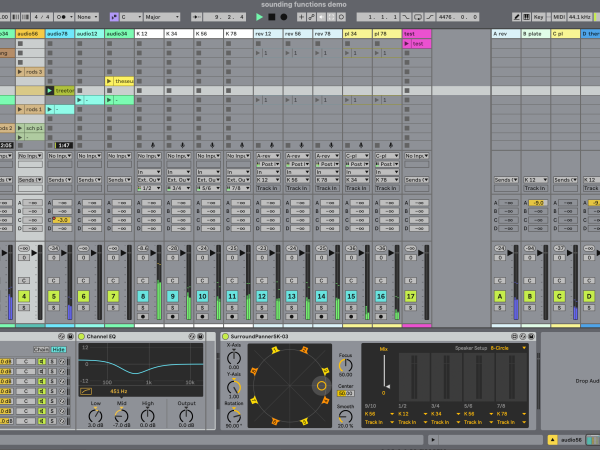

I was always interested in composing long sounds and wanted to remove any sense of pulse from the music I wrote for acoustic instruments. I had been doing this with electronic music performance for a while, without notation. I had looked at how composers struggled with traditional notation when attempting this – repeated semibreves tied together across bar lines, rapidly changing time signatures and hard-to-make-sense-of subdivided groupings of dots on a page. I began drawing lines as notation, and eventually, with my collaborators in Decibel, we found a way to coordinate these lines so that they could be read as notation by the ensemble (Ingold, p22, 2016). This led to the design of the Decibel ScorePlayer, a tablet application that amongst other things, puts images in motion at a pre-determined speed across a playhead which marks the point of performance. This system started a flourish of creativity for me – I had found a way to notate the ideas I had been developing in my head, so I have a very personal experience of the liberation alternative notations can provide.

In the development of my first opera Speechless (2019), I wanted to incorporate singers from different musical styles, and in the orchestra of low-frequency instruments, performers from different backgrounds. I quickly realized that my notation approach facilitated this – and by assigning groups of instruments a color, and describing duration, pitch, texture, and form in the score, everything else took care of itself as I was prepared to give all other decisions away to the performers. I also added improvisational sections to enable various musicians to showcase their style – or whatever they wanted to showcase - which the Decibel ScorePlayer provided a time frame for. The biggest challenge has been to remind musicians that there is still flexibility in what some describe as a ‘martial’ score reading system (Rosenfeld, 2021) – just as with other notations, you still need to communicate, synchronize, and gesture with other musicians. Screens seem to demand attention (Klatt et al), but music is a good tool to subvert that tendency.

Access

These projects have got me thinking about how digital scores can facilitate access to music reading in a way common practice notations have not. Dynamic colors, movement, and low-frequency pulses embedded in or triggered by the score provide methods to enable score readying by those with different sight and hearing abilities. But for now, the biggest challenge is to make musicians from other styles welcome to the music reading process. My recent work VOLUMINUM (2023) combined rock musicians with classical ones, we all read the score together on networked iPads, shared with the audience via a large video screen behind us. In telematic performance experiences of my work with countries outside the West, I found musicians adapted quickly to my dynamic, graphic notations. This tells me that you can enlarge the musical family around score reading if we are ready to accept more freedom around elements that have previously been so fixed in tonal, pulsed-orientated music. This speaks to new, collaborative approaches in composition and performance, as I wrote about in the New Virtuosity Manifesto with Louise Devenish.

Not all music needs notation

There is still a place for melody and harmony, and we have the tools to notate it. But what about those sounds not yet devised? New ways of performing together? Whilst I acknowledge not all music is, can be, should be, or will be notable, much of the music being made today is. When devising new works with French composer Eliane Radigue (I have been involved in three) it is immediately clear that her ideas are best shared personally through listening, discussion and performance, and these works will live on through interpersonal transmission. Similarly, my bass noise performance practice cannot be notated, and as a fundamentally improvised practice of my own, it would serve no purpose to do so. But a lot of contemporary music relies on recordings as a way to reproduce work into the future, despite this only providing skeletal information toward recreating this music together.

There is real possibility and potential in alternative music notations that enable musicians of different styles and backgrounds to play together. By developing music notation designed to encourage more performer contributions, expressions of contemporary musicianship and composer’s ideas, there may be a place for music reading into the future. Music reading can retain a valuable role in today’s musical practices, we just have to find the right approaches to facilitate it.

Cat Hope

Cat Hope is an award-winning Australian composer and performer who focuses on the extremes of sound – from extreme noise to barely audible delicacy. Her works have been performed worldwide by ensembles such as Yarn Wire (US), Hanatsu Miror (FR), the BBC Scottish Symphony (UK), KNM (DE), and Norbotten Neo (Sweden). Recordings of her works are published internationally on labels such as Hat (Hut) Art, with her monograph CD Ephemeral Rivers winning the German Critics Prize in 2017. Her music has been discussed in books such as Score Writing (Thor Magnusson, 2019) and Hidden Alliances (Schimmana, 2019), as well as periodicals such as The Wire (UK), Revue & Corrigée (FR), Neu Zeitschrift Fur Musik Shaft (DE) and Gramophone (UK), who named her “one of Australia’s most exciting and individual creative voices.” Cat is also an active music curator and academic. Her recent book, co-edited with Louise Devenish, “Contemporary Musical Virtuosities” (Routledge, 2004) has been called “a rewarding, thought-provoking book” (Stefenakis, 2024), and her co-authored book ‘Digital Arts: An Introduction to New Media’ (Bloomsbury, 2014) was described as “brilliant in its relevance and succinct accessibility” (Young, 2017). Cat is the director of the Decibel new music ensemble, who pioneer the interpretation of digital and animated notations for music.

Article topics

Article translations are machine translated and proofread.

Artikel von Cat Hope

Cat Hope

Cat Hope