10 Minuten

Introduction

Close your eyes and let your ears (and imagination) take over — well, not so much for this article, but when you try out your first audiogame experience! An “audiogame” is a video game that has no graphics or visuals, where the player uses solely their hearing to learn skills, navigate environments, conquer enemies, solve puzzles, and win. Some AAA games offer accessibility mods that let those without sight play some or most of the game, but the importance of visuals in those games is still the driving sensory experience. A true audiogame removes the visual sense completely and focuses on the other sense that can be delivered through a desktop computer or game console: hearing.

Over the past several decades, a small but passionate community of experimental game developers have released audio-only games for desktops, mobile, and the web, with standouts being Papa Sangre (2010) and A Blind Legend (2016). With no visuals to rely on, audiogames need to solely leverage sound design, audio cues, music, voice dialog, and DSP techniques to create game mechanics and game levels. A common technique of many of the most popular audiogames is the use of binaural spatial audio to help create convincing audio environments and diegetic sound cues. Achieving this sense of audible reality is core to the player trusting their ears to play and win and becoming fully immersed in the game’s world.

Earlier this year I released my very first indie game for PC and Mac on the Steam platform called Rocococo Audiogame Fantastique and I’m excited to elaborate on my experience developing it and how spatial audio is a key component of the design.

How My Journey Prepared Me

I probably would not have endeavored to take on such a feat as creating and designing an audiogame were it not for 2 essential aspects of my career and years of audio-technology pursuits: making games and spatial audio. Over the past 25 years as an electronic musician and composer, I have always been enamored with how technology can facilitate unique, immersive, and interactive sonic experiences. I have been fortunate to spend a decade dedicated to creating music-based videogames and another decade dedicated to advancing and evangelizing spatial audio technology.

At Harmonix, a game studio based in Boston USA, I spent 13 years as an Audio Director, Producer, and Game Director working on interactive music-game franchises like Guitar Hero, RockBand, and Dance Central. Working there taught me the skills to create, design, and produce games that let non-musicians feel like rock stars. Through countless prototypes and experimentation, myself and the team there found unique ways to abstract a musical experience and distill it into a fun and rewarding game experience.

After working on games, I was ready for a new challenge and found myself pivoting careers into spatial audio technology; first at Microsoft on the HoloLens spatial computing platform and most recently at THX heading up product development for their suite of spatial audio offerings. I also began creating my own music-VR apps for Oculus Rift and Meta Quest devices where 6doF plus spatial audio technology was employed to build interactive sound environments. Through these activities, I worked closely with DSP and acoustical engineers to understand and improve the technology, learn how it’s employed and optimized on various platforms, design the tools needed for creators to utilize the technology, and craft best-practices for how to get the most out of a spatial audio experience.

- Download my free music-VR app (m)ORPH.

- Or check out footage of the (m)ORPH VR app here:

With ample knowledge of what it takes to create a video game and how to best leverage spatial audio to craft immersive audio experiences, I was ready to fuse those together to create my first audiogame. My only other goal was to design a game where adding visuals to the game would detract from the experience and further cement sound as the essential component.

Dive Into the Dark and Turn Up the Volume!

The creation of “Rocococo Audiogame Fantastique” took about 20 months to complete. It was built upon the Unity game engine and FMOD audio middleware engine, and involved 3 Unity engineers, 2 voice actors, 1 story/script writer, and countless friends and colleagues for QA testing. For my part, I devised the game concept and designed the game, concocted the world it’s based in, composed all the music and sound design, and integrated the audio into FMOD. The game uses the Oculus Spatializer spatial audio FMOD plugin to handle all the binauralization of the music, sound design, VO, and environmental sounds in real-time. All of the story cutscenes used pre-rendered binaural mixes created using the THX Spatial Creator DAW plugin.

- Want to create binaural mixes for your music, game, or media projects? Grab the free trial of THX Spatial Creator.

The best first step with any new game idea is to quickly prototype the core game loop – essentially the main actions you perform in the game and upon which all other game design decisions are based. If those basic game mechanics are not simultaneously fun and challenging, then you’re probably not on the right path. I knew that I didn’t want to create a rhythm action game (think Guitar Hero) where you tap along with a visual or audio cue as accurately as possible. I wanted my music-game to be more about locating hidden tracks of audio from a song and re-assembling them, while avoiding harmful obstacles, all solely using your ears.

Within just a few weeks I had a functioning Unity prototype that I was able to share with the supportive community at www.audiogames.net with feedback from blind, visually-impaired, and sighted players. This crucial feedback helped me understand what was working and what wasn’t so that I could refine the experience as much as possible. One element that was not working well in the prototype was having too many sounds around you, all making noise and clamoring for your attention. This sonic cognitive overload was something I was going to have to pay careful attention to. Fortunately, the main action of hunting around and using your ears to locate tracks of audio around you worked… and was both challenging and fun!

Spatial Audio at the Core of the Design

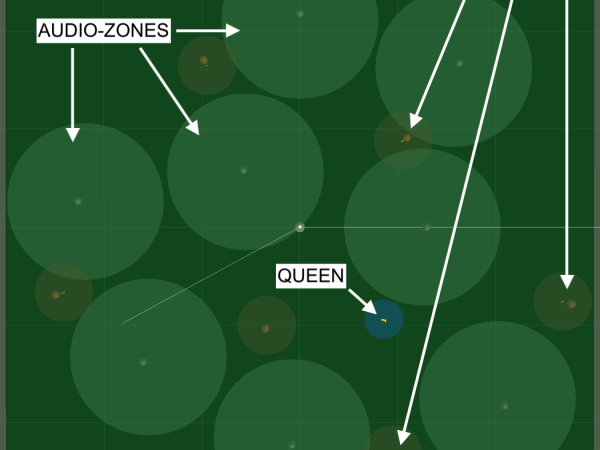

The main premise of Rocococo is that each of the 13 game levels is a song which has been sliced up into its individual elements – snare, kick, hats, bass synth, lead synth, arp synth, etc. Some levels only have 6 tracks while the harder levels have between 15-20 different tracks. The player is in a room (completely dark, with no visuals) and the audio tracks are randomly placed around the room. The player’s goal is to locate those tracks, aka audio-zones, and navigate to them. When they are as close as possible, you capture them with a key/button press and are scored on accuracy. At the end of the level, the better your zone-capture accuracy, the higher the score. Every track is a binauralized sound object, all with the exact same distance-based volume curves. These distance curves were carefully selected and tuned so that you can hear only the closest 2-3 audio-zones around you. This lets you quickly locate the nearest one, center on it and run towards it.

The HRTF-based binaural audio lets players clearly know if a zone is to the left or right, and when the player centers the audio, they know it’s right in front of them. Running towards the zone makes it louder and running away makes it quieter, just like sounds in the real world. This basic use of spatial audio is the key technology that allows the game to function and players to trust their ears. Additionally, the level is filled with sound objects that can harm you like static and stationary robots that can inflict damage to the player; 1-3 hits by a robot, and you have to start the level over! Sometimes there is an evil Queen who shows up and chases you around and can “off with your head” so the player keeps an alert ear out for her presence. All the harm-bots and Queen are binauralized so the player has a concrete sense of where they are located and how far away they are. The levels are then tuned with all these spatialized sound objects placed at distances that make the levels easier or harder to play. As the levels get more difficult, there are more audio-zones to locate, while avoiding many closely-spaced robots to carefully navigate around.

The Pesky Limitations of Spatial Audio

For those working closely with spatial audio, we’re keenly aware of the many limitations of the technology; from generalized HRTF’s not working well for everyone, to tonal coloring, to elevation issues where sounds don’t believably sound above or below you. This was also the case in my game and I had to make some design decisions and sonic adjustments to help improve elements where the spatial rendering was lacking. The very first design decision I made, even before prototyping began, was to eliminate the need to look up or down, or have the player move to high or low locations where sound needed to be spatialized anywhere other than the azimuth. This decision lets spatial audio work at its best, on the level plane around the head, and also lets the player simply focus on audio-objects around them on that same plane. Probably the biggest issue with spatial audio for my game was that I was binauralizing music tracks, all with different frequency and amplitude characteristics. Bass synth and kick drum tracks weren’t spatializing well due to low frequencies, while certain resonant synth tracks were overloading and causing distortion at certain distances. Additionally, the Oculus Spatializer plugin doesn't handle near-field processing which added to the problems when you got very close to the emitter position.

I had to utilize other sound techniques in addition to spatial processing to help the player locate these musical audio-zones with high degrees of accuracy. One aspect that was challenging players was knowing when they went past (or through) an audio-zone and it was no longer in front of them, but now behind them. The spatial audio would correctly place the sound emitter behind you from a rendering POV, but the tonal change was too subtle and players would not notice the change. To help emphasize when zones were behind you, I employed a low-pass filter that would kick in immediately if you went past the emitter. The further you went past it, more higher frequencies would get removed. By tuning this filter’s parameters, it became more crystal clear to the player when a zone was in front or behind them.

Another aspect of the game where spatial audio was falling a bit short and needed some reinforcing was with the harm-bots. These vengeful robots are scattered throughout the level, with some being static and others moving around. Each harm-bot had a looping audio track of them saying a line of VO dialog over and over. These audio emitters were also being spatialized but while it was clear to the player where they were (left, right, in front, or behind you), it was not precise enough in knowing how far away from you they were. At a certain distance they would harm you so players knew they needed to keep some distance away, but spatial audio alone wasn’t giving them this distance cue.

Thus, in addition to spatializing their audio I added a second looping layer of spatialized audio, this time a nasty-sounding SFX track that sounded like a mixture of an alarm and robotic bleeps and bloops. This secondary loop was the sound that alerted the player to immediately move away or get attacked. This dual-audio system was tuned so that the VO layer could be heard starting at a distance of 6m which helped the player identify where the harm-bot was but not necessarily be in danger, and then the “danger” SFX loop would ramp up more quickly at a 3m range. The Queen character who occasionally chases the player around is also spatialized and the combination of both her VO audio events and running footsteps SFX were just enough for players to know when she was around. Her VO event system would also switch from far away VO lines like “where are you? I know you are here somewhere!” when she was 8m away or more, and then switch to a different VO tree at less than 8m with lines like “I’m hot on your heels” and “I’m so close I can catch you” indicating to the player to get further away from her.

What’s the Future of Rocococo Audiogame Fantastique?

The game was officially released on the Steam platform worldwide (see link below) and my hope is to next bring the game to other gaming platforms like consoles and VR. I’m most excited by VR as that’s the 6doF platform where spatial audio really shines as you have all those head micro-motions helping to dynamically update the diegetic sound positions. Additionally, having controller haptics could add another dimension to gameplay and help support and reinforce hearing-based gameplay. I’m also happy to see fresh and exciting spatial audio solutions coming from new developers. I’m eager to experiment more with those and see what opportunities they can bring to an immersive audio experience.

- Get the Rocococo audiogame from Steam.

- Interested in a deeper dive into audio-only games? Check out this Game Developers Conference talk by Brian Schmidt.

I encourage all game creators to get out of their comfort zone and experiment with creating a game that leverages other senses and also be cognizant of how our games and apps are used by those with limited sight, sound, and motor-skills abilities. Making games accessible to all brings a lot more players into the joyful world of gaming – grab your headphones and let’s play!

Kasson Crooker

Kasson Crooker is an audio-technologist focused on creating interactive experiences at the intersection of music and technology. Over his 30-year career, he has helped produce music video games like Guitar Hero and RockBand as well as music-VR apps like (m)ORPH and Saturnine. He has helped evangelize spatial audio technologies at companies like THX and Microsoft. An accomplished musician, Kasson has scored an indie film and released over 20 albums of electronic music in various styles.

Article topics

Article translations are machine translated and proofread.

Artikel von Kasson Crooker

Kasson Crooker

Kasson Crooker