13 Minuten

Introduction: urban sound, engagement and spatiality

Unless we walk through life wearing noise reduction headphones, we need to explore ways to engage with our urban soundscape. Sound affects us both positively and negatively; the urban sound environment can stimulate stress or comfort, boredom or interest, engagement or disinterest, a want to stay and a want to leave. For both inhabitants and visitors the sound environment forms societal rules that we may keep and break. I appreciate silence in my life; I know some people cannot sleep without the hum of traffic outside their window. After decades of being sidelined, noise abatement and noise-sensitive city planning has gained points in governmental agendas. Sound type and not only absolute energy levels also now has some bearing.

For the majority of city inhabitants, when the noise doesn’t actively annoy us, we try to ignore it as we go about our daily activities. However, amongst the noise can be found intriguing features that may tempt a different listening strategy. This information is hidden from us either by way of acoustic masking, or because it is an artefact of a more salient action that has a more prominent position in our perception, or simply because we have become so familiar to it we no longer care to listen. If we become interested in these features, we may overcome some of the negative experiences of urban noise and feel a sense of space, place and presence. In the urban sound landscape, to know what to preserve, what to improve, or simply to feel more present and positive, implies that we need to manoeuvre our listening to be interested, or at least engaged. But manoeuvring our listening in this way is not easy. This is where my work with 3D sound-art and the urban landscape enters.

The complexity of the urban soundscape and the dense overlap of spectral information makes it particularly challenging to study compared to natural habitats, where nature finds its own spectral niche as a communication channel. What we do know is that when sounds are spatially separated we can mentally process more information by virtue of our spatial hearing. We also know that listening to recorded sound out of context gives time to explore its features, and is one of the fundamental approaches to electroacoustic composition. Yet in urban environments, the spatiality and the impact of sound propagation, which is a critical aspect of our daily experience, remains poorly understood, and composers interested in the soundscape tend to gravitate towards the tunes of nature rather than the noise of culture.

3D audio technology and the 3D sound landscape

Few microphones can capture ‘space’ as well as our best spatial hearing, where the angular spatial resolution varies depending on the angle of the sound to our ears and the spectrum of the source: at best a few degrees of spatial difference in the frontal area of our head, at worse, many degrees above and to the back of the head (and this is why we move our head to help us hear where a sound is coming from). At the time of writing, the MhAcoustics 6th order ambisonics EM64 is the only commercially available product that can maybe do this. But unlike our non-uniform spatial hearing, 3D microphones capture sound equally from all directions. So maybe we can consider using less accurate 3D microphones, such as the MhAcoustics 4th order ambisonics EM32 or the 3rd order Harpex spcmic. In my own experience, frequency response and noise floor, as well as spatial resolution, are all important considerations when making equipment decisions.

I refer to ambisonics several times in this article, and my work methods are based on the ambisonics approach to spatial sound. For readers unfamiliar with ambisonics, it is a two-part process of recording or synthesising 3D sound information, and then decoding this information to loudspeakers or headphones. Information is represented in what are called spherical harmonics, where the more spherical harmonics used (the order of ambisonics), the more accurate the representation of the spatial sound-field. There are many online resources for further reading, but be aware that the top hits on Google when asking for ‘ambisonics for beginners’ have been taken over by companies promoting their own hardware, or studio guides that are hardware specific. For a beginners read I would suggest Matthias Kronlachner 2012 and Barrett 2021b. For a comprehensive and technical read: Zotter et al. 2019.

If we have the ability to record at a high spatial resolution, we need to decide how to use this information. We definitely cannot listen to the recorded resolution over just a few loudspeakers in our studios! For all formats, high spatial resolution in playback means increasing the number of loudspeakers needed. What we can do is to ‘decompose’ the 3D recording into its directional and diffuse elements - as our hearing does so well already - to reveal a more complete picture of the sound landscape. We can then use this spatial decomposition as a starting point for analysis and musical exploration.

Using this method I propose that we can draw attention to interesting features captured in the recordings, and with a science-art approach to information and composition, entice and provoke a new awareness of what is present yet hidden from everyday listening. I have tested this hypothesis in five artistic case studies with the following workflow:

- 3D site-specific recording.

- 3D sound analysis.

- Composition to draw into the perceptual present features we many find interesting.

- Layering this composed 3D soundfield into the site from which the source was taken.

Here I will introduce the longest running outdoor experiment “PRESENCE | NÆRVÆR”. I will then present an example of relocating these outdoor sound experiments indoors; an environment where we deny the listener the sensory stimuli of the original real-world context.

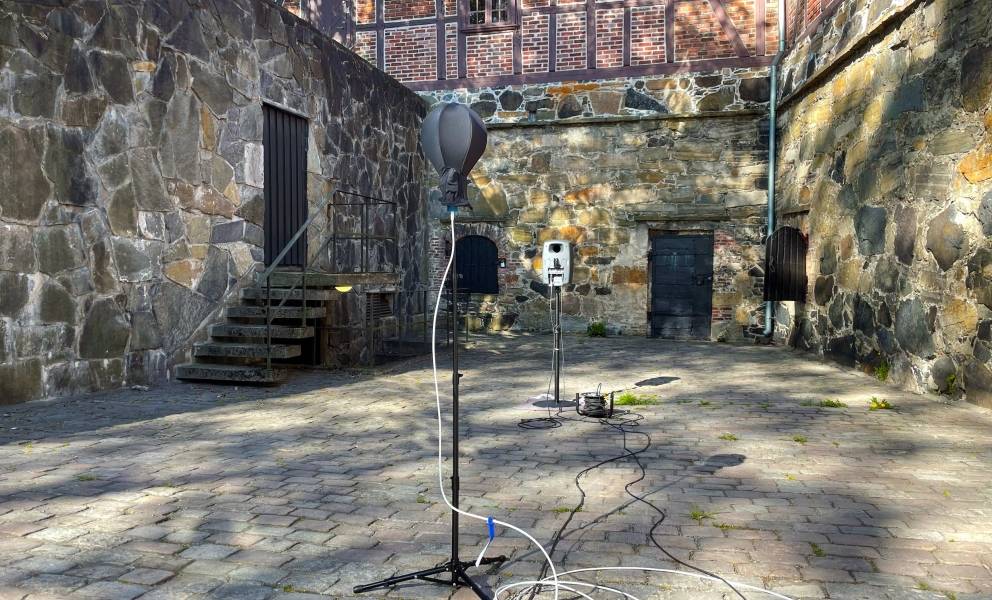

PRESENCE | NÆRVÆR outdoor sound installation, Akershus Fortress, Oslo. Left: small loudspeaker detail. Centre: main courtyard. Right: beam-forming loudspeaker detail.

PRESENCE | NÆRVÆR

What if we make the background foreground? What if the sounds of the past resonate through the present? What if the hidden details, the disguised features, the traces and the artefacts, break out of the everyday noise we tend to ignore and tell a story of space, place and presence?

PRESENCE | NÆRVÆR was an outdoor, site-specific sound installation that explored these questions. It was created as part of the Norwegian artistic research project 'Reconfiguring the Landscape', hosted at the Norwegian Academy for Music and funded by the Norwegian Agency for International Cooperation and Quality Enhancement in Higher Education (DIKU). The installation was realised in collaboration with Akershus Fortress and Stiftelsen Akershus Festning for Kunst og Kultur (SAKK), and was also part of the Ultima Festival and Oslo Culture Night.

The installation was located in the courtyard outside the Resistance Museum at Akershus Fortress, Oslo. It played through all weather conditions from 7:00 to 21:00 every day, from September 16th to November 2nd 2022. The courtyard is cobbled and framed on three sides by heavy stone walls, creating an interesting acoustic fingerprint evident when you clap or shout. On one of these sides is a grassy bank with tall deciduous trees, and on the fourth side, which is also the entrance, there is a low stone wall, a hedge, and beyond that it opens out to a larger area of fortress grounds.

As the seasons change, the soundscape undergoes various transformations. Species of birds come and go, winds roll in from the harbour playing with the trees in full leaf and streaming through their bare winter branches. An expansive area of the city and harbour is within earshot. City noises come and go, diffusing in a variety of ways with temperature, snow coverage, and wind direction.

Sound capture and ecological theory

Source recording. Left: inside the courtyard. Right: on the other side of the fortress wall.

Sounds were recorded from various positions within the courtyard area over a 6-month period using the MH-Acoustics EM32 microphone. Some recordings were made in February, while the majority were captured from March to June 2022. Extended durations of sound were recorded to capture the temporal variation of the soundscape, including intermittent sounds, repeating sounds, keynote sounds (familiar sounds heard above the background), and the continuously varying background hum of the city and harbour.

The approach to source collection was inspired by the ecological theory of Eleanor and James Gibson, which has more recently been elaborated by Tim Ingold (Ingold 2000) and others. In Barrett 2021 I discuss how Ingold questions why, in soundscape composition, we artificially slice up the environment based on the unique location of our microphone or along a soundwalk that we may take. Instead, he argues that "the world we perceive is the same world, whatever path we take" and that "place" is not a space occupied by things but rather a woven habitat that we understand through motion: existence unfolds, affected by encounters with the surroundings where knowledge is gained through movement that unravels what is called "the meshwork." There are many interesting things to say about Gibson, Ingold, and the wave of perceptual psychologists and anthropologists that have followed. However, that is the topic of a different article, and here we are interested in how these ideas affected my recording and composition practice for the sound installations.

My theory is that we may overcome problems of transient participation by recording for a duration beyond our normal period of stay, and from many spatial locations. In other words, to achieve in recording what is impossible for a short-stay visitor. Also, as the microphone records uniformly from all directions we are already removing directional bias.

In addition to recording the soundscape, I also captured the acoustic environment, or in other words, I recorded 3D Impulse Responses (IRs). These were created using a Genelec 8050 loudspeaker, an MhAcoustics EM32 microphone, and the Spat5 Sweep Measurement Kit. Through a process called convolution (which, in simple terms, involves multiplying the spectrum of two sounds), I can make a dry sound appear as if it is emanating from the new space. IR convolution will be most familiar to readers in the form of reverberation effects plugins that emulate the acoustics of indoor spaces. Outdoor acoustics are more subtle, and the reverberation tail vanishes very quickly, but they are also very useful. By convolving the on-site recording with the on-site IR, the perceptual volume of the real reverberation can, to some extent, be controlled (although there will be some blurring as reflections are multiplied by reflections). In this way, I can more clearly reveal the acoustic fingerprint, which may be less obvious in natural listening.

Composition

The recordings were analysed using two methods: computer-based feature recognition, also known as 'computer listening,' and traditional 'composer listening.' While the workings of computer listening can become quite technical, simply put, we either instruct the computer to listen for specific information in the space, spectrum, or temporal domain, or we ask it to ‘learn’ about the sound through machine learning and neural networks. In contrast, composers traditionally follow an autoethnographic approach to their sound—that is, a process guided by listening and decision-making based on experiential self-reflection.

When considering ecological theory and working with extended recordings, we are limited by the ear’s and body’s variable awareness. After an hour or more of listening, a decision I make one day may not be the same as if I carried out the same procedure another day. This implies that the autoethnographic approach is prone to failure. With computer listening, we can achieve greater consistency. However, this, in turn, may come at the expense of potentially interesting details that the computer ignores. Combining both methods can result in a balanced outcome, revealing one-off features and main archetypes. In the analysis, I devised a method to separate multiple simultaneous sources and their motion features from the 3D recording. This process outputs individual streams of mono sounds and spatial data. In addition to isolating clear features, I can alter the spatial-frequency spectrum to reveal information usually masked in noise. In composition, I decide when and how to enhance interesting elements and musically reflect the natural sound environment’s changing spatial and temporal event fingerprints. (The technical and theoretical aspects of this work are discussed in Barrett 2021 and 2019).

PRESENCE | NÆRVÆR Onsite

Layering the musical result back into the site required technical pragmatism. Instead of a high-density loudspeaker array, the installation is played over eight all-weather loudspeakers, allowing only a 3rd order 2D ambisonics space, and a special prototype loudspeaker that directs beams of sound toward the surrounding surfaces.

The simplest way to hear the work now it has been removed from the site, is a stereo mix that I made for home listening. This mix includes a little of the original background sound to set the scene. It features on the Reconfiguring the Landscape CD release, along with stereo mixes of some of the other installations: https://natashabarrett.bandcamp.com/album/reconfiguring-the-landscape

More interesting for this article is to show an onsite recording made on the evening of the 16th September and at noon on the 1st November 2022. For the September recording the weather was fine and it was possible to record the audio with the MhAcoustics EM32 microphone placed in the centre of the courtyard, which you can see on the video. For the November recording there was heavy rain, and the audio was recorded on my phone with the video. (Documentation video recorded on the evening of the 16th September and at noon on the 1st November 2022.)

Despite the relatively 'low' resolution spatial playback, the combined result of real and added elements seemed to function well. Many people, including school parties, contemporary music festival delegates, and ordinary individuals, listened for extended periods. In a questionnaire accessible to visitors via a QR code, over two-thirds stood in the cold for more than 20 minutes and reported that it changed their experience of the normal soundscape.

The Sound Worlds exhibition: relocating the outdoor works into an exhibition space

As a conclusion to what became a three-year research project, three of the five installations were remixed for an indoor exhibition space as a multi-part work called “Sound Worlds.” “Sound Worlds” was installed at the Old Munch Museum in Oslo and was open to the public from the 24th to the 26th of October 2023.

To capture the spatiality of the outdoor installations, this indoor exhibition was equipped with 43 speakers arranged in an 18-channel 3D dome and a 25-channel surround array. Although the site-specific installations were played only in 3rd order 2D ambisonics, I had the foresight to compose in 7th order 3D. This higher spatial resolution is crucial for recreating the spatial experience indoors—a situation where we lack the full sensory experience and need to compensate by providing the ears with much more information.

The three works ran in a continuous loop lasting approximately 40 minutes:

- Remote Sensing on the Beach (2020)

- Presence | Nærvar (2022)

- Impossible Moments from Venice 1 and 2 (2023)

The only visual information consisted of simple lighting in the speaker dome, natural light penetrating the ceiling, the speakers, the bare space itself, and five large 360-degree photos taken at different sites featured in the pieces.

Sound Worlds 360 pictures: Top, Top left: Oslo fjord winter. Top right: Oslo fjord summer. Bottom left: Venice fish market. Bottom right: Venice tower.

Two views of the installation space with speaker dome and surround loudspeaker array.

The public could enter at any time and stay as long as they wished. Most people stayed longer than the complete loop.

Summary

Outdoor sound-art installations ultimately involve working on someone’s doorstep. Whether experienced as an intrusion or welcomed, it can be a delicate balance of volume, content, engagement, and communication. As artists, it's easy to forget that the majority of the population does not engage in contemporary art, and what we perceive as music, many may perceive as noise. In a project addressing the urban sound landscape, this raises an interesting question: are we negatively adding to the noise or creating a positive experience? "Presence | Nærvar" was installed long enough for all kinds of people to stumble upon it. Tempting people to complete questionnaires about their views is not easy and most responses coincided with the two weeks of the Ultima contemporary music festival, which is a somewhat positively biassed audience. I however visited the site regularly outside of festival time, and on one occasion a middle-aged couple had stayed for some minutes and I asked what they thought. They answered that it was “noise” to them, but that it was “interesting noise” which made them curious. Not wanting to probe complete strangers, I left them to walk on. In another installation that I haven’t talked about in this article, an old man was moving, pausing, moving and pausing. I asked what he thought, and he said it was like a nature-filled forest but made from city sounds.

Natasha Barrett

Natasha Barrett composes concert works, public space sound-art installations and multimedia interactive music using a broad palette of sounds, new technologies and experimental techniques. She is widely known for her electroacoustic and acousmatic music, and use of 3D sound technology in composition. Her work is commissioned and performed throughout the world and has received over 20 international awards including the Nordic Council Music Prize and most recently the honorary Thomas Seelig Fixed Media Award for 2023. She regularly collaborates with performers, visual artists, architects and scientists, and is active as a performer of live-electronics and spatial audio.

Article topics

Article translations are machine translated and proofread.

Artikel von Natasha Barrett

Natasha Barrett

Natasha Barrett