12 Minuten

The world of modernity is a world that is understood visually, a signifying of what is seen. Movements in this environment are seen as a generalization of one's movement because of the power of the body and are causally evaluated as a world of "shocks and thrusts" (Levy 2000). The dominance of this worldview also led to the dominant mediatization of physical movement in robotics and corresponding embodiments in language-based logic as artificial intelligence and has thus transcended this mechanistic worldview. The Anthropocene describes this one-sided wo/man-made culture. The body has remained, but the hedonic body, the one that moves from the experienced tension through movement in the environment to survival - this is the paradigm of phylogenetically older hearing, which in this mediatized culture "forward back" becomes essential for survival again. Bio-semiotics now give this natural knowledge cultural meaning.

At the same time, the mediatization of the body has led to technologies that specifically capture its movements. The knowledge of the body-sound connection now makes it possible to move sound directly. Beyond the instrumentarization of the body, the body itself becomes an "instrument". Controlled by its excitement, it forms sound and communicates this (beyond time and space) with other bodies. Thus, for the first time, music is created that does not distinguish different cultures in a power struggle, but rather a unifying music of all bodies, of all people based on the dominant force of life, physical arousal formalized in hearing.

The future will be sounding - it will "function" according to the paradigm of hearing sound as movement and the excitement of movement and its communication - it is, therefore, a culture based on the nature of physicality. It is a hedonic as human digital culture. In this bio-political democracy, music connects the world beyond the stereotypical image of the "logic" of a common language in a primal sentence in the commonality of the primal survival force of the body in the hedonic - excitement.

The arts as a formalization of perception

Traditional arts can be seen as cultural formalizations of the specificities of sensory-bodily perception. These specificities are developments of evolution, their formalizations are instrumentarizations and mediatizations. Above all, seeing and hearing can be regarded as extreme forms of the human near and far senses - they differ fundamentally in the movement of the body in the "reception" of the environment, as well as in the development of the cerebral cortex and thus the processing of stimuli.

Seeing makes it possible to grasp the psychological moment. Passing through the environment the body creates a series of images (as reflections of light on the texture) of the environment as visual fields in front of the body. Cognitive processes of the cerebral cortex enable the signifying of what is seen, in front of which the seeing body stands, and thus its "under-standing". The artistic image formalizes the view of the moment, and the film a moving series of images. Both are linked to understanding or are deliberately shaped by "understanding". In narrative film, sound serves the function of structuring and emotional charge of "signs", but even early video art brings the dynamization of the image according to the paradigm of hearing into the mediatized image world, which itself does not sound (Jauk 2006).

Hearing is the perception of the movement caused by sound around the motionless body. Sound can only be perceived in time and primarily "abstractly" (Carmiaux 2011). The concrete designation (signifying) as an attribution to a cause is the result of previously direct or indirect visual perception or its "narration" as cognition. Nevertheless, sound has meaning, namely as meaning for the body: sound as movement generates arousal, which in turn sets the body in motion (for its survival). Bio-semiotics refers to this as "animal semiosis" (Kull 2009). The instrumentarization of this performative movement makes music-making possible, its mediatization is formalized in music.

What was initially taken away from music by the mediatization of bodyness through writing becomes now an "unmediated" body-sound-dynamic that can be shaped and experienced through media technologies close to the body.

Furthermore, it is an adequate form of cultural perception in mediatized worlds (Jauk 2013).

The transgression of the mechanistic - the hedonic of mediatized forms of life according to the paradigm of music-making

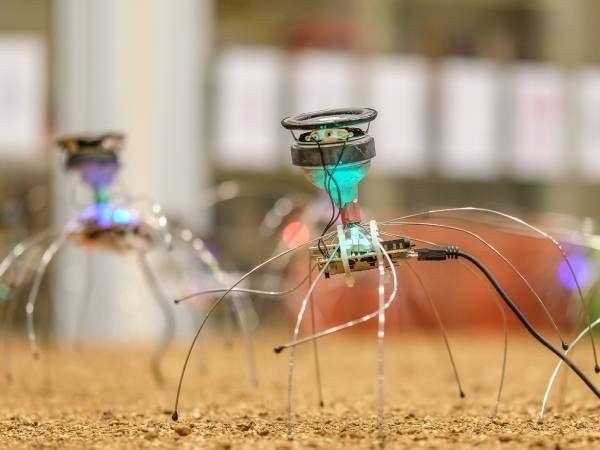

The modern culture of understanding vision and the mechanical movement of the body has primarily mediatized these functions of perception. This reflects the one-sided understanding of perception as a cognitive process (of seeing) and the interaction with the environment as bodily mechanical movement. Their mediatization led to the extension of the human being and thus to the creation of visual forms of thinking about the environment and to the extension of his mechanical skills in robotics. Ultimately, this one-sidedness made the (mechanical) body "useless" (Baudrillard 1981). It also led to the "feasibility" by thinking not only of social, but also of physical worlds beyond natural limitations and to the Anthropocene.

Thus, mediatization - above all through the dynamization and virtualization of the environment - led to the transgression of the mechanistic system and to the transgression of the embodiments created by the physical interaction of humans with the physical environment, which determine the "way of seeing" as a way of thinking about the environment formalized in language (Jauk 2009). The consideration of hearing as a highly developed remote sense not only comes close to the requirement of the complete agent (Maturana 1987), but hearing now proves to be an adequate form of interaction (Jauk 2009). The hearing body perceives "movements" in the environment, it does not "interpret" them mechanically "rationally", but perceives them as meaning for the body as excitation. Hearing is thus the paradigm of intentional body-environment interaction (Gibson 1982). Perception is thus bodily action according to intention in the original sense of "tension" of the body due to movement in the environment. It was not until the Enlightenment that intention went from "being in tension" to "having in sight" (Mauthner 1923) and thus to a cognitive decision about "things" and their "behavior", which mediatized worlds now elude through the mediatization of the mechanical body and thus of ways of thinking from its embodiments. In the "all-at-onceness" (McLuhan 1995) of mediatized worlds, the hearing body perceives "movements" according to their meanings for the body and in turn communicates this meaning physically - perception in dynamized virtualized worlds of the mediatized mechanical body, its embodiments and the ways of thinking that arise from them adequately follows the hearing interaction.

Sound-gesture - perception as intentional body-environment interaction

The concept of sound gesture is central to this: sound is an artifact of movement in the environment. The body perceives sound and its modulations as an imagination of movement around it, which arouses it and thus moves it (Jauk 2014, 19, 21). This movement from arousal is directly communicative through "emotional contagion" (Hatfield 1994). The experience of moving bodies sets other bodies in synchronous motion. The perception of (being) touch(ed) and music, and ultimately hearing as touch, are likely to have led to close neuronal processing in evolutionary terms. The connection to common movement can also be explained by this and proves to be a social technology of evolution.

See and hear, "touch the sound"

See and hear, "touch the sound" Ars Electronica 2015

e-mot-ivat-ion - Feeling the Ex-Tension

e-mot-ivat-ion - Feeling the Ex-Tension, Ars Electronica 2017

Generally, medium levels of arousal are experienced as pleasant, while arousal that is too high or too low is gradually avoided to achieve a middle level (Berlyne 1973), which phylogenetically ensures survival. "Emotional contagion" reinforces this behavior as a common one.

In addition to the left-right perception by the two ears, the imagination of the movement of sound is based on the perception of modulations through distance and thus temporal changes of the sound within the psychological moment as spatial depth perception. The perception of height is to be interpreted as a "conceptual metaphor" (Lakoff 1993) of gravity (Jauk 2014, 19, 21). High sounds are perceived as having "high density" and "less volume" (Stevens 1965) and therefore as "above", low sounds are perceived as having "less density" and "high volume" (Stevens 1965) and therefore as being "below" (Jauk 2014, 19, 21). Although sound itself eludes perceptible gravity, this basic body knowledge is transferred as a concept to the perception of sound.

Knowledge of the interplay between the parameters of the sound and the excitation, and even the emotional assessment, now and in the future allows a combination and thus simulation of the perception of the movement-excitation sound - without physical spatialization of the sound itself solely through the modulation of the sound (Jauk 2018) and for direct physical music-making (Jauk 2016, 19, 21).

The emotional communication of intentional bodies beyond time and space

Now it is technical extensions of the human being that directly enable physicality beyond linguistic mediation and dynamically create a common sound world from the movements of the participants. Motion-tracking (in whatever technical form) is the mediating "technology" as a psychophysical interface. It is not about capturing (mechanical) movement, but the specifics of movement that indicate certain forms of excitement. The interface here is the empiricism of the relationship between movement and sound through arousal. Motion-tracking allows the conversion of physical tension and release into sound as social interaction in the here and now, but also beyond time and space. The storage/transmission of body sound as a mood quality from partners into one's own environment creates "emotional closeness despite physical distance" (Jauk et al. 2021)

See me, feel me, touch me ...

hear me & heal me ...

See me, feel me, touch me ... hear me & heal me ... Ars Electronica 2021

It also allows emotional interaction with materials, the generation of psychological qualities of spaces from the recognition of movements of humans within (even public) spaces for their psycho-hygienic optimization, for the creation of an iHome (Jauk 2015, 16)

iHome

iHome,Ars Electronica 2015

The music-making of in-tention-al bodies - an emo-political syn-biosis of cultural bodies

What was limited to the shared experience of cultural peculiarities in the bourgeois concert business is now becoming part of everyday life.

The availability of "technologies" brings these forms of interaction and creation into a "new amateurism" (Prior 2010) of/for EVERY BODY (Jauk 2019, 21). The music of bourgeois political emancipation turned domestic music into a power "game" by making the orchestral "Werk" music of royalty learnable via the piano score and making it resound in the salon via the piano as a mass instrument. In popular music, the guitar and the playing of memorized music in symbiosis with a political connection to its politically oppressed original creators created a sense of unity. However, the German translation of the term populär was avoided due to its distinguishing use in the German Reich. Electronic and digital music completely abandons the idea of the uniqueness of the "Werk" and its (also expropriating) political "sign" (Eco 1985) and becomes the dynamic music-making of an emotionally moving acoustic driving and thus worldwide "popular" music. It exists without pre-writing, conducting, or even without a "master" of a non-self-determined ceremony (since it is ultimately autocratically staged as a culturally conditioned event), without AI as an artificial initiation - less intelligent than emotional (Jauk 2019b). In this, it is not distinguishing, but together based on the general "bodyness" of humans, independent of culture - it lives a bio-politics of democracy, individually together, without time and space.

An "auditory culture" (2019a), formalized in bodily music-making, is the livable paradigm of a culture from nature from the needs of the bodies. It is thus a culture of overcoming nature through the will of the powers, formalized in language, and thus a culture of overcoming the construction of "reality", which is conceived from the dominance of the one-sidedness of seeing and the signifying of what is seen as "understood".

This means that the future is sounding. Not only because of the composition/componere by digital processing of the material sound beyond cultural rules, but because of a dynamic completely beyond cultural ideas of conceived material formations. The future is a formation of sound from the tension of the body and its movement generated by it as well as the co-movement of other bodies. It is a syn-biosis that is inherent to all human bodies - of different cultural origins.

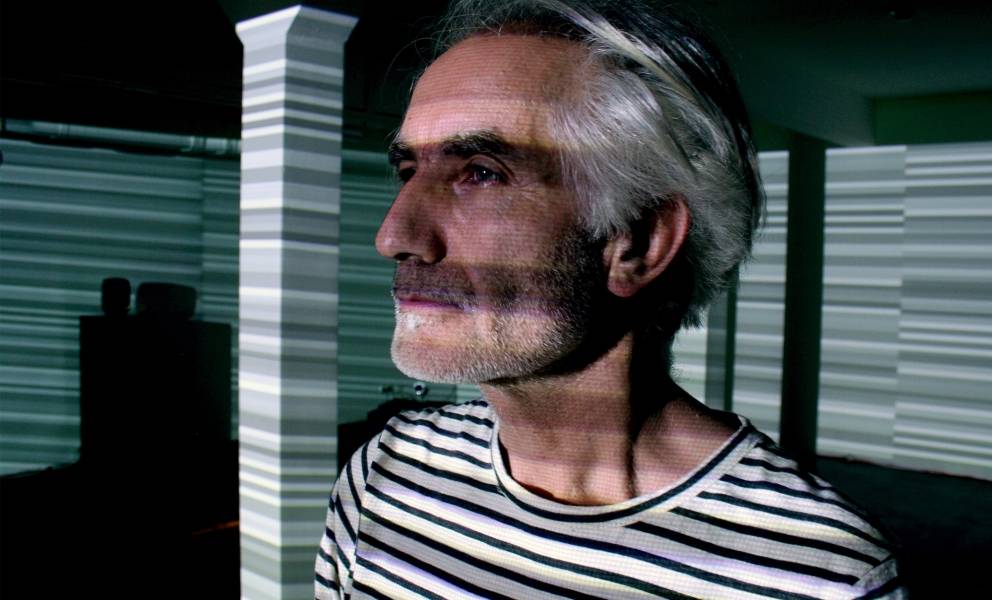

Werner Jauk

Werner Jauk is director of Ars Electronica Research Institute "auditory culture". He did his Phd in psychology (musical cybernetics, information theory and aesthetics, music-perception & AI), early as well as postdoctorial studies (jazz-guitar, computermusic) at KUG-Graz and IRCAM-Paris and his habilitation in musicology (pop / music & media / art) always focusing on auditory perception and its mediatisations as cultural processes of the formation of music and media cultures. His interdisciplinary scientific research has been published in scientific monographs, journals and congress papers C https://homepage.uni-graz.at/de/werner.jauk/publikationen/); reserach-projects between science and art are part of media art festivals (from ICMWT International conference on Mobile & Wireless Technology Beijing, ETH - Zurich, InstituteNewMedia - Frankfurt, CyNET-art - Dresden, Styrian Autumn & Liquid music - Styria, Biennale di Venezia Architettura et Music to Ars Electronica etc. (a selection - see lists of publications and lectures as well as artistic researches https://homepage.uni-graz.at/de/werner.jauk/publikationen/). Finally, this interdisciplinary research and Multi-Media-Art lecture-activities on EU-universities led to the establishment of the study focus "pop music and media culture" in the inter-university MA-studies "Musicology" at KUG and KFUG and to the establishment of a transmedial research institute AERI- "auditory culture" at Ars Electronica. https://aeri-auditoryculture.at/

Article topics

Article translations are machine translated and proofread.

Artikel von Werner Jauk

Werner Jauk

Werner Jauk