17 Minuten

Technological information . . . rests on a substratum of machinery that is becoming concealed from the understanding of those who operate on its surface. The blackboxing that is the consequence of progress in information technology encloses ever larger spaces of hardware and software. It is an unavoidable development. The larger black boxes support more powerful tools. – Albert Borgmann, Holding on to Reality

The inner workings of consumer electronics and information technologies are increasingly concealed as a result of the development of newer generations of technologies. Devices are built out of existing technologies, and in the process, the components fade from being contemplated objects into the background of infrastructure.

When mature and deployed widely, technologies are understood by users as objects that serve a particular function: a doorbell makes a sound when pressed; a telephone makes a telephone call; and a photocopier outputs a document without much complex technical negotiation. The inner workings of the technical thing are unknown to the user, with the circuitry of the device acting like a mysterious “black box” that is largely irrelevant to its use. It is only an object with a particular input that results in a specific output; its mechanism is invisible. From a design perspective, the technology is normally designed to render the complex mechanisms invisible and usable as a single punctualized object.1 As a part of this evolutionary process, black boxes are the punctualized building blocks from which new technologies are built.2

Bending Black Boxes

A black box, however, is a system that is not intricately understood or accessed, and as a result, obsolete or broken technologies are often unusable. Once the product stops working, the device is often unrepairable and inaccessible by the average consumer. Unlike a household lamp which can be fitted with replacement light bulbs, many consumer electronic devices have no user-serviceable parts, and the object is discarded after it breaks. The depunctualization, or breaking apart of the device into its components, is difficult due to the highly specialized engineering and fabrication processes used in the design of the artifact: electronic technologies are typically engineered to be discarded instead of repaired. However, artists, musicians, and other DIY practitioners frequently take technological obsolescence as a starting point for their work. Obsolete objects are regularly disassembled, rewired, and repurposed for different applications than what they were originally designed, and in the process, the black boxes are “bent” into new forms.

Ghazala and the Origins of Circuit Bending

Artists, musicians, and creative individuals probe and explore obsolete technologies in ways that expand our standard notions around what is technologically obsolete or useful. Old computers, vinyl, cassette tapes, or pieces of retro musical equipment are reused, repaired, and remixed with newer components. Media artists and creative hackers regularly manipulate and customize technologies for the fun of exploring the technological system, often breaking apart and reverse engineering without formal expertise, manuals, or a defined endpoint. One noteworthy figure on this topic is Reed Ghazala, a Cincinnati-based American artist born in the 1950s. He has been pivotal in the formation of the practice of “circuit bending.” The DIY technique of circuit bending takes found objects like battery-powered children’s toys and creatively repurposes them into spectacularly original musical instruments and homemade audio generators.

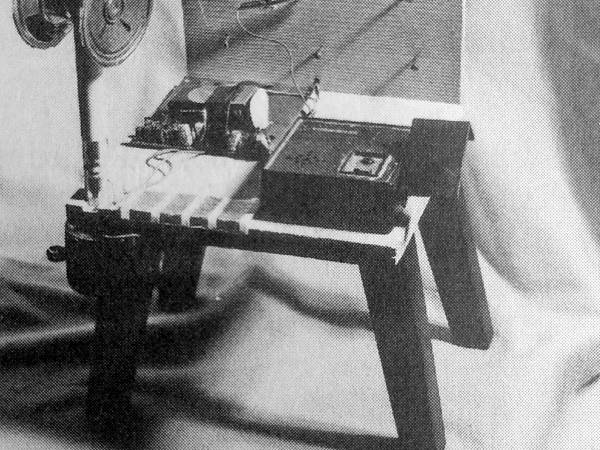

Circuit bending, a term coined by Ghazala, is a methodology for modifying inexpensive secondhand circuits that he first explored in Ohio in the late 1960s. The origin of his method came as the result of a random amplifier malfunction that occurred while he was a high school student (figure 2.1.1):

In my drawer a small battery-powered amplifier’s back had fallen off, exposing the circuit. It was shorting-out against something metal causing the circuit to act as an audio oscillator. In fact, the pitch was continuously sweeping upward to a peak, over and over again. I soon modified the amplifier in numerous ways. Placing the circuit within a larger housing, I added rotary switches to the short circuit paths so I could run the new circuits through various resistors, capacitors, diodes, photo cells, and any other electronic component I could find. Potentometers and push-buttons were added. I discovered places on the circuit that, if touched, would make the circuit howl.3

Bending developed as an experimental and unpredictable process to reuse, reappropriate, and customize scrap electronics, placing value on highly randomized results, immediacy, and the discovery of the undocumented or the concealed. The aesthetics of circuit bending are quirky, handmade, and one-of-a-kind, and practitioners value the entire process of developing and exploring, not just the end result.

Figure 2.1.1 Ghazala’s reconstruction of his first circuit bent instrument, circa 1967–68. The original was destroyed by “an irate audience” during a performance. Source: Reed Ghazala, Circuit-Bending: Build Your Own Alien Instruments (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 2005), 8.

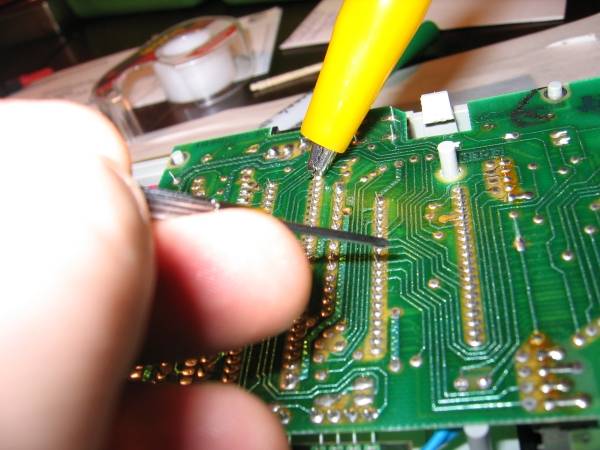

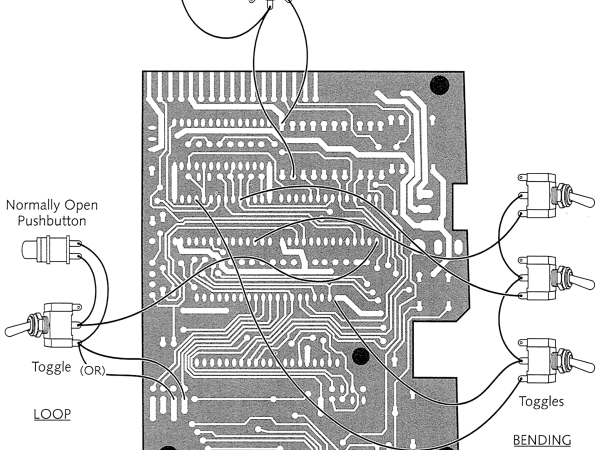

The process of circuit bending typically involves going to a secondhand store or garage sale to obtain an inexpensive battery-powered device, taking the back cover of the device off, and probing the mechanism’s circuit board. Any two points on the circuit board are then connected by using a “jumper” wire that temporarily short-circuits and rewires the device (see figure 2.1.2). Any conductive piece of metal will do; Ghazala used a bent hairpin in his early experiments. The battery-powered device is on during this process so the artist can hear the results of their probing, which is causing electric current to be rerouted in ways the device was not originally designed for.

Figure 2.1.2 The process of probing for “bends,” where a jeweler’s precision screwdriver electrically connected to an alligator clip is used to probe soldered connections on the back of a circuit board.

If an interesting result is found, the connections are marked for modification, and switches, buttons, or other devices can be inserted between these points to enable or disable the effect. Optionally, the connections can be modified to be sensitive to touch: conductive metal pieces can be soldered to the points as “body contacts,” where the performer simultaneously touches both connections and has the low-voltage electricity flow through their body to enable the effect. This process of exploratory reverse engineering continues on a trial-and-error basis over the circuit board: probing, locating bends, and intervening in the circuit. The joy of discovering sounds and effects that are concealed in the system is part of the allure of the process, and when multiple bends are combined, the bent systems often become unpredictable, shifting and recombining. The end result is the handmade customization of a device that might have been considered obsolete.

It should be noted that several historical precedents for both musical chance encounters and electronic musical experimentation existed long before Ghazala, including those from people like Leon Theremin and Maurice Martenot – with their electronic gestural instruments – and John Cage, who began using chance procedures in 1951.4 Nam June Paik famously bent the electrons of a tube TV in 1965 with Magnet TV.5 Ghazala’s unique contribution can be seen as combining these variables and articulating a methodology for them through disassembled postconsumer devices.6

Hacking Speak & Spell: The Incantor

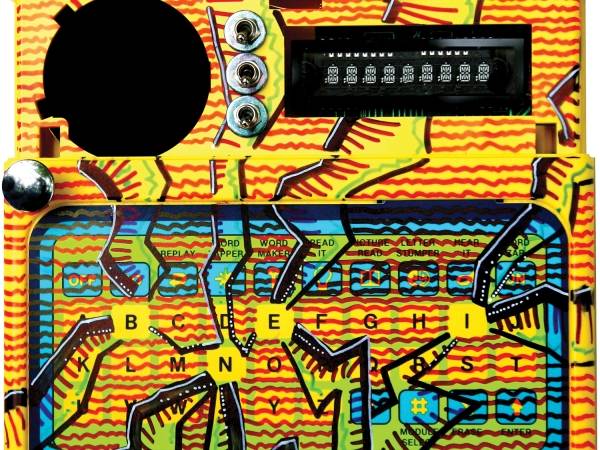

Likely the most recognizable and iconic example of circuit bending is Reed Ghazala’s Incantor series of devices, commonly known informally as “hacked Speak & Spells.” Ghazala has been building these highly customized Speak & Spell, Speak & Read, and Speak & Math children’s toys since 1978 (figure 2.1.3). As an outgrowth of Texas Instrument’s research in the area of synthetic speech, the Speak & Spell learning toy was designed to educate children aged seven and older in how to spell and pronounce more than 200 commonly misspelled words.7 However, Ghazala’s Incantor completely reconfigures the synthesized human voice circuitry to spew out a noisy, glitchy, tangle of sound that stutters, loops, screams, and beats (figure 2.1.4).

Figure 2.1.3 An Incantor, a modified, or “circuit bent” Speak & Read, by Reed Ghazala. First devel- oped in 1978. Courtesy Reed Ghazala.

“One of my modified Speak & Reads, in a voice that sounds like an intoxicated Jack Benny, occasionally says ‘Let’s smell the scissors s’more’ . . . [and some] of the sounds are indescribable, but an example might be: ‘Ayy’ – bell sound – pitch sweeps – ‘oh’ – metal crash – bubble sound.”8

Similar to the early twentieth-century artists who employed readymade materials, Ghazala sees the surplus of consumer devices as an “immediate canvas” that can be simply modified to discover a mysterious, surreal world of sound.9 Although the junk culture of reuse is consistent between early twentieth-century readymade artists and contemporary circuit benders, there is a distinct difference in present-day work: bending takes a unique pride in the folk process of reverse engineering without formal expertise and prizes one-of-a-kind inventions. As opposed to Marcel Duchamp taking a machine-manufactured product and positioning it, almost sarcastically, as a handmade piece of art, this work rejects the machine-manufactured aesthetic of the source product and alters it into an idiosyncratic and crafted piece. The mechanically reproduced original device is taken from a generic form and hand tuned into a feral kind of invention, introducing a sense of aura, or a unique “presence in time and place.”10 This is achieved through the process of bending, a type of contemporary ceremony where a hidden underlayer is explored, perhaps reminding us of Walter Benjamin’s belief that “the unique value of the ‘authentic’ work of art has its basis in ritual, the location of its original use value.”11

Communities of Error

Circuit bending, as promoted by Ghazala and others, has developed over the last few decades into a diverse network of practitioners, with semianual international festivals dedicated to the topic running since at least 2004.12 The community of circuit bending feeds off of inexpensiveness and immediacy. In comparison to other electronic techniques, circuit bending is a simple and straightforward electronic audio design process that requires minimal prior knowledge of electronics. The continued proliferation of consumer electronics has made the raw materials of circuit bending ubiquitous, with folk knowledge around circuit bending practices increasingly dispersed over the Internet, in magazines, and through local hackerspace workshops (figure 2.1.4).

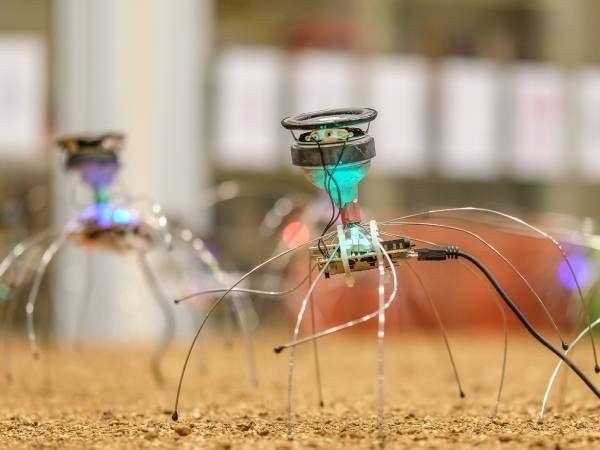

Critics of circuit bending, like Jeff Morton, raise several valid concerns about the scene. For one, only considering Reed Ghazala as the sole “father” of the field cuts off clear historical precedents, like Leon Theremin, Ondes Martenot, and John Cage. Although the term “circuit bending” is useful, it also contains some danger. Blindly adopting Ghazala’s origin story can establish a cult-like scene with Ghazala at its core and limiting the field of practice to his style of work. One example of this influence can be seen in the similarity and even conformity of circuit bending events, workshops, and performances. As Morton outlines, “My work with circuit-bending has become refined to the point where I recognize similarities and idiosyncrasies in basically every electronic toy I encounter. There are many permutations and a practically infinite variety of interconnections, but it is always contained within the parameters of the original system.”13 Although the events celebrate aleatoric chance encounters, the formula is, ironically, predictable. Events often feature a table with a bunch predominantly white men poking around the circuits of broken-apart, battery-powered toys (figure 2.1.5).

Figure 2.1.4 Circuit bending diagram for a membrane-keypad Speak & Spell circuit board that forms part of the Incantor. Source: Reed Ghazala, Circuit-Bending: Build Your Own Alien Instruments (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 2005), 219, fig. 15–2. Courtesy Reed Ghazala.

Demanding Depunctualization: Hackability, the Right to Repair, and Open Source Hardware

Circuit bending and similar practices take the trash of electronic culture as a starting point, and its key tactic of reuse is driven by a punk-like breaking apart and exploration of blackboxed consumer technologies. Sociologygist and anthropologist Anne Galloway identifies that DIY practitioners have the ability to create their own worlds through DIY methods like circuit bending: “Similar ethics and practices can also be found in punk rock ‘do-it-yourself’ (DIY) cultures.

Figure 2.1.5 Back DVD cover image from Bent, Derek Sajbel’s 2004 documentary about the first International Circuit Bending Festival (NTSC, 150 minutes). Courtesy Derek Sajbel.

The general premise behind DIY is that if you do not like the way things are done, then you should do it yourself. DIY culture involves creating your own world amid the dominant culture, thereby putting power back in the hands of individuals.”14 DIY culture uses available, inexpensive materials to shape one’s own cultural identity by building what one feels is missing from the mainstream – your own album, your own book or magazine, your own clothes, or your own musical instrument.15 “Around the world, people are making things themselves in order to save money, to customize goods to suit their exact needs and interests, and to feel less dependent on the corporations that manufacture and distribute most of the products and media we consume.”16

However, for circuit bending and DIY practices involving information technology, a problem lies with the blackboxing and planned obsolescence of technology. Contemporary methods of manufacturing and planned obsolescence result in devices that are not only difficult to modify, but also intentionally engineered to be difficult to modify; although the devices are inexpensive, they are inaccessible, and their interiors are generally the territory of experts. The affordance of user serviceability in many electronic devices has been systematically removed to save space, weight, or cost, or to encourage users to replace instead of repair the products.

Demanding serviceable or modifiable technologies is not only an effort to lengthen the projected lifespan of consumer products, but is also viewed as a deeper issue of ownership and of blurring the demarcations between consumers and producers. This demand has been termed by some authors as an appeal for “hackability” – for consumer devices that are depunctualizable, explorable, reconfigurable, and customizable.17 Hackability is also intertwined with the important topic of repairability, which can be seen as a legal, technical, and environmental issue through governmental initiatives like the “Right to Repair” bills. Politicians like Massachusetts Senator Elizabeth Warren have proposed legislation to protect farmers from being bound to proprietary repairs for agricultural equipment: “Newer John Deere equipment comes loaded with software and firmware that make it impossible for farmers to fix their own equipment. Broadly speaking, right-to-repair legislation would have a measurable impact on the average consumer’s life, from the farmers hacking their tractors to people suffering from sleep apnea who tweak their CPAP machines to folks who just want a decent price on a replacement iPhone screen.”18 In summary, the blackboxing of technology can be defined as “a process that makes the joint production of actors and artifacts entirely opaque,” and hackability can be seen as a desire to make product actors and artifacts more visible and revealed.19

A key component of electronic DIY culture relates to the values of open-source software and to extending these values to manufactured electronic hardware devices. In the open-source mindset, a hackable device has fewer corporate dependencies when it fails. Systems are better when they are technically accessible and nonproprietary, and when they include relevant documentation to assist in the modification of the device. Unlike computer software, no End User License Agreement (EULA) for hardware usually exists; instead, the device is physically constructed with technical barriers that limit nonexperts from accessing the mechanisms inside of it.20 Ed van Hinte envisions this as two territories of ownership of a device: the exterior skin of a product that is touched and owned by consumers, and an interior that belongs to somebody else. “This segregation into territories is quite peculiar. The person who buys a vacuum cleaner or a walkman does not have the entire purchase at one’s disposal. Yes, you can unscrew it and open it up – if you understand how to do this, that is, which might be quite a puzzle – but your attempt will be punished by loss of your guarantee, and in the case of some larger appliances you may even be threatened with death.”21

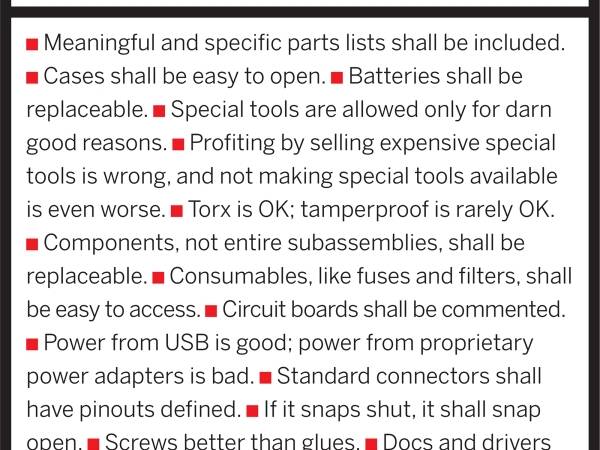

Taking the lead from open-source software advocates, Make magazine and other organizations position hackability as an issue of consumer rights and ownership.22 Specific design and manufacturing processes – like glued-shut cases, the ease of repair of devices, a lack of documentation, the requirement of proprietary tools for repair, and proprietary batteries or chargers – are violations of consumers having outright ownership of their hardware (figure 2.1.6). This concept of ownership can be summarized by the slogan “If you can’t open it, you don’t own it”: when products break down, hidden power structures, dependencies, and infrastructures are revealed. To use Heidegger’s terms, dependencies come forward when an object shifts from being ready-to-hand to being present-at-hand.23

Breaking apart and getting inside a piece of hardware usually shows a network of dependencies that tie the owner to the corporation that manufactured the device. Thacker and Galloway state that “you have not sufficiently understood power relationships . . . unless you have understood ‘how it works’ and ‘who it works for’. It is not only worthwhile but also necessary to have a technical as well as theoretical understanding of any given technology.”24 A hackable device, in this sense, has fewer dependencies than the average black box when ripped apart, or “depunctualized.”

Bent Conclusions

As a theme, a significant cluster of DIY electronic practices focus on unpacking and exploring the “black boxes” of technology and changing the taken-for-granted function of the technology without formal training or approval.

Figure 2.1.6 Make magazine’s Owner’s Manifesto, a bill of rights to accessible, extensive, and repairable hardware. Source: Make magazine issue 4 (2005).

Circuit bending, then, is an electronic DIY movement focused on manipulating circuits and changing the taken-for-granted function of the technology without formal training or approval. In de Certeau’s terms, “These ‘ways of operating’ constitute the innumerable practices by means of which users reappropriate the space organized by techniques of sociocultural production.”25

In the practice of opening up black boxes, error and malfunction typically spill out, but these malfunctions can be bent, transformed, and amplified into features. In other words, a black box is opened and broken apart, producing components that are disorganized, jumbled up, and without- out an explicit use, which then results in errors and trash that are creatively twisted into use.26 Circuit benders work with the exploded fragments of broken technologies, in other words. These fragments can be more pleasing to the creator than the original role of the device, and in the case of circuit bending, errors become the prime feature of the modified device. Error – in some ways – is the willingness to let materials and technologies play their own role or to have efficacy in the creative process.27 As Greg Siegel discusses in Forensic Media on the topic of black boxes, cybernetics and communication theory have historically viewed noise as something to be canceled – although the invention of the flight voice recorder changed that. Often noise is the most information-loaded component recorded when catastrophe hits.28

In summary, circuit bending is a way of operating that reminds us that users consistently reappropriate, customize, and manipulate consumer products in unexpected ways, even when the inner workings of devices are intentionally engineered to be the zone of experts. Reed Ghazala’s Incantor is useful as a tool to remind us of sociotechnical issues in contemporary society, including planned obsolescence, the blackboxing of technology, and the interior inaccessibility and ownership of everyday consumer products. As a way of operating, circuit bending is an aspect of digital culture that does not fit under the term “new media” or in standard frameworks of innovation. The customized and folksy DIY methodologies of circuit bending recall a pre-new-media attitude of handmade craft and a post-new-media recycling of surplus electronics. DIY electronic practices like circuit bending clearly bend more than electronic circuits; they creatively prompt us to rethink the sociotechnical issues of planned obsolescence and the complex layers of ownership within digital culture and artifacts.

Chapter 2.1 from Art + DIY Electronics by Garnet Hertz, reprinted courtesy of The MIT Press.

- 1

Punctualization refers to a concept in Actor-network theory to describe when components are brought together into a single complex system that can be used as a single object. For more information, see Bruno Latour, Pandora’s Hope: Essays on the Reality of Science Studies (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1999).

- 2

For a relevant discussion of infrastructure, see Susan Leigh Star and Karen Ruhleder, “Steps Toward an Ecology of Infrastructure: Design and Access for Large Information Spaces,” Information Systems Research 7, no. 1 (1996): 111–34; and BernardLondon, Ending the Depression through Planned Obsolescence (New York, 1932), https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/006829435.

- 3

Qubais Reed Ghazala, “The Folk Music of Chance Electronics: Circuit-Bending the Modern Coconut,” Leonardo Music Journal 14 (December 1, 2004): 97–104, https://doi.org/10.1162/0961121043067271.

- 4

James Pritchett, The Music of John Cage (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1993), 94.

- 5

Edith Decker-Phillips, Paik Video (Barrytown, NY: Barrytown, Ltd, 1998).

- 6

Ghazala, “The Folk Music of Chance Electronics,” 97–104.

- 7

Texas Instruments, “TI Talking Learning Aid Sets Pace for Innovative CES Introductions,” press release, June 11, 1978, http://www.datamath.org/Story/TI_PRESS.htm.

- 8

Reed Ghazala, “Incantors,” Anti-Theory, accessed August 19, 2021, http://www.anti-theory.com/sales/sales_gallery /c/main.html.

- 9

Ghazala, “The Folk Music of Chance Electronics,” 97–104.

- 10

Walter Benjamin, The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction (London: Penguin Books, 2008), 220.

- 11

Benjamin, The Work of Art, 220.

- 12

“Bent Festival 2009,” archived April 20, 2009, https://web.archive.org/web/20090420052844/

http:/www.bentfestival.org/. - 13

Jeff Morton, “A Critical Perspective on Circuit-Bending,” BlackFlash, May 16, 2013, https://blackflash.ca/2013/05/16/circuitbendingjeffmorton/.

- 14

Anne Galloway, Jonah Brucker-Cohen, Lalya Gaye, and Elizabeth Goodman, “Design for Hackability,” in DIS ’04:Proceedings of the 5th Conference on Designing Interactive Systems: Processes, Practices, Methods, and Techniques (New York: ACM Press, 2004), 364, https://doi.org/10.1145/1013115.1013181.

- 15

Amy Spencer, DIY: The Rise of Lo-Fi Culture, 2nd ed. (London: Marion Boyars, 2008), 11.

- 16

Ellen Lupton, ed., D.I.Y.: Design It Yourself, Design Briefs (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2006), 18.

- 17

Galloway et al., “Design for Hackability,” 364.

- 18

Matthew Gault and Jason Koebler, “Elizabeth Warren Calls for a National Right-to-Repair Law for Tractors,” Vice, March 27, 2019, accessed August 20, 2021, https://www.vice.com/en/article/d3mb5k/elizabeth-warren-calls-for-a-national-right-to-repair-law.

- 19

Latour, Pandora’s Hope, 183.

- 20

For an analysis of software End User License Agreements, see Cory Doctorow, “Shrinkwrap Licenses: An Epidemic Of Lawsuits Waiting To Happen,” Information-Week, February 2, 2007, https://www.informationweek.com/software/shrinkwrap-licenses-an-epidemic-of-lawsuits-waiting-to-happen.

- 21

Ed van Hinte, et al., eds., Young Designers Trigger Industries Trigger Young Designers (Amsterdam: De Balie, 1996), 226–227.

- 22

Initially published by O’Reilly Press starting in 2005, Make spun off into its own corporation as Maker Media Inc. in 2013. For more information, see “Make: Community,” Make: Community, accessed August 20, 2021, https://make.co.

- 23

In Heidegger’s terminology, the ready-to-hand is a tool that is used intuitively and as an extension of oneself without being focused on as an object, while an object that is present-at-hand is objectively present and requires the user to think about it as an object. Martin Heidegger, Being in Time, trans. John Macquarrie and Edward Robinson (Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishers Ltd., 1962), 99. http://pdf-objects.com/files/Heidegger-Martin-Being-and-Time-trans.-Macquarrie-Robinson-Blackwell-1962.pdf.

- 24

Eugene Thacker and Alexander R. Galloway, introduction to Protocol: How Control Exists after Decentralization, Leonardo (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2004), xiii.

- 25

Michel de Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life. 1, trans. Steven Rendall, (Berkeley, CA.: Univ. of California Press, 2013), xiv.

- 26

John Scanlan, On Garbage, repr. (London: Reaktion Books, 2005), 14–16; and Greg Siegel, Forensic Media: Reconstructing Accidents in Accelerated Modernity (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2014).

- 27

Emit Snake-Beings, “The DiY [‘Do It Yourself’] Ethos: A Participatory Culture of Material Engagement” (PhD diss., University of Waikato, 2016), 12, https://hdl.handle.net/10289/9973.

- 28

Siegel, Forensic Media.

Garnet Hertz

Garnet Hertz is Canada Research Chair in Design and Media Arts, and is Associate Professor of Design at Emily Carr University. His art and research investigates DIY culture, electronic art and critical design practices. He has exhibited in 18 countries in venues including SIGGRAPH, Ars Electronica, and DEAF and has won top international awards for his work, including the Oscar Signorini Award in robotic art, a Fulbright award, and Best Paper Award at the ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI). He has worked as Faculty at Art Center College of Design and as Research Scientist at the University of California Irvine. His research is widely cited in academic publications, and popular press on his work has disseminated through 25 countries including in publications like The New York Times, Wired, The Washington Post, NPR, USA Today, NBC, CBS, TV Tokyo and CNN Headline News.

Article topics

Article translations are machine translated and proofread.

Artikel von Garnet Hertz

Garnet Hertz

Garnet Hertz