I was recently sitting at the harbor of a small fishing village in southern Italy. The fishermen, legs apart, with their hands in their pockets, turned their backs to the street and looked down into the sailboats that had just come home from their catch. It was very quiet, but suddenly there was hissing and spitting behind me, a screeching, screeching, whistling sound - the radio was being activated, its loudspeaker embedded in the front wall of the café. It was used to catch customers. What the net was to the fishermen, the loudspeaker was to the café owner. As the screeching faded, an English announcer could be heard speaking. The fishermen turned around and listened, even though they didn't understand. The announcer said that they would now be broadcasting German folk songs for an hour and that he hoped the listeners would enjoy them. And then a typical German men's choir sang the old songs that every German knows from childhood German from London, in an Italian village where hardly any foreigners ever come. (Rudolf Arnheim, Broadcasting as an Art of Listening)

Almost a hundred years ago, with the spread of radio and records, the electronic reproduction of sound and music gradually found its way into everyday life and changed the habits of making and listening to music. As the media philosopher Rudolf Arnheim so vividly described in 1939, this was also accompanied by new devices: the loudspeaker became an everyday object and the embodiment of modern music consumption. Hardly any other sound generator is as widespread, and hardly any other medium has influenced social practices of communication and listening as strongly as the device that was first described and built in 1878 by Werner von Siemens as an electro-acoustic sound transducer. Loudspeakers have long been present not only in settings dedicated to listening to music or public communication - but they are also so ubiquitous that we often hardly notice them and don't think about whether and why the sound we are listening to is coming from a loudspeaker. And I find them fascinating precisely because of their ordinariness and simplicity.

A loudspeaker in its function as a sound transmitter initially directs attention away from its visible self towards the actual listening experience, similar to how, in the course of the so-called concert reform at the beginning of the 20th century, attempts were made to conceal the performers behind curtains and screens in concert halls to realize an ideal of "pure" listening, without visual distractions caused by the musicians' gestures, which were perceived as disturbing. Such ideas of a pure, purified music-making and listening practice beyond the imprecision and imperfection of human beings also shaped the discourse surrounding the development of acousmatic and electroacoustic music from the 1950s onwards. The loudspeaker and the sound machinery behind it were stylized in a transhumanist manner as the ideal image of a better-than-human performer. In the loudspeaker orchestra performances of the acousmatic tradition, the hearing of sound can be experienced as a differentiated spatial action in a way that a human orchestra could not realize.

Without loudspeakers, to put it bluntly, there would probably be no sound art as an art form, which, not coincidentally, emerged near the development of electronic sound technologies and celebrates the experience of sound as a moment of perception. Listening to loudspeakers is, therefore, the opposite of what the composer Michel Chion described as ergo-audition, as "listening to oneself", namely:

„... das Hören dessen, der den gehörten Klang gleichzeitig auf die eine oder andere Weise verursacht oder auf diesen einwirken kann. [...] Wir haben es mit ergo-audition zu tun, wenn der Zuhörer gleichzeitig, teilweise oder zur Gänze, bewusst oder unbewusst, für den Klang, den er hört, auch verantwortlich ist: indem er ein Instrument spielt, eine Maschine bedient oder ein Fahrzeug lenkt, Geräusche verursacht – durch seine Schritte, seine Kleidung, seine Bewegungen oder Handlungen, indem er Flüssigkeit in ein Gefäß gießt oder auch indem er spricht.” (Michel Chion, 1988)

Michel Chion himself was not only a composer of acousmatic music, but he was also concerned with the theory and philosophy of technically mediated listening situations in electronic music and film. Listening without a visible sound source played an important role in his concepts and theories on film music.

Not only as an object in its materiality and design but also through its function and through the effects that listening to technically reproduced sounds has on people, the loudspeaker is far more than a technical tool - it is a cultural and psychological artifact, it is a sound transducer, an auditory and sensory transducer at the same time. Loudspeakers, as sound artist Cathy van Eck summarizes, are not only mediators of sound, but they also interfere in aesthetic processes of perception, generate new forms of musical and artistic production, their practices, and ways of dealing with them and create new ways of listening.

The separation between physical sound production and perception, between sound source and (electromechanical) re-production is sensually embodied in the loudspeaker: what sounds from loudspeakers is not necessarily related to what is otherwise audible and visible in the listener's immediate surroundings, even if the directness of the sound may suggest a physical presence. The resulting gap between the senses makes us aware of listening as a relational, cross-sensory process: a dialog between the human ear and the mechanism, between the existing sound environment and the artificially created sound space, between the eye and the ear, as well as between our external world and our internal auditory movements. The loudspeaker shifts our perception and thus also our own position as human listeners; it directs our attention away from egocentric perception to the sound as an actor. This double play between being located in one's own environment and immersing oneself in a virtual auditory impression has become all the clearer since mobile sound devices such as the Walkman and its technical successors have become established as mass products. The mobile loudspeaker as an everyday companion creates its own way of listening, drifting, and drifting between being physically in the place and being seduced by the imaginary sound space that stretches out around our ears. Listening to loudspeakers in public spaces creates a subtle kind of audiovisual schizophrenia, an embodied intervention in the auditory-social fabric of an environment, which the Japanese sociologist Shuhei Hosokawa aptly described as the "Walkman effect".

What techniques and behaviors influence the way we listen in everyday life? Changing listening cultures - this podcast was created as part of the "Grazer Soundscapes" project and documents a soundwalk that Justin Winkler and I designed together for the Grazer Kunsthaus.

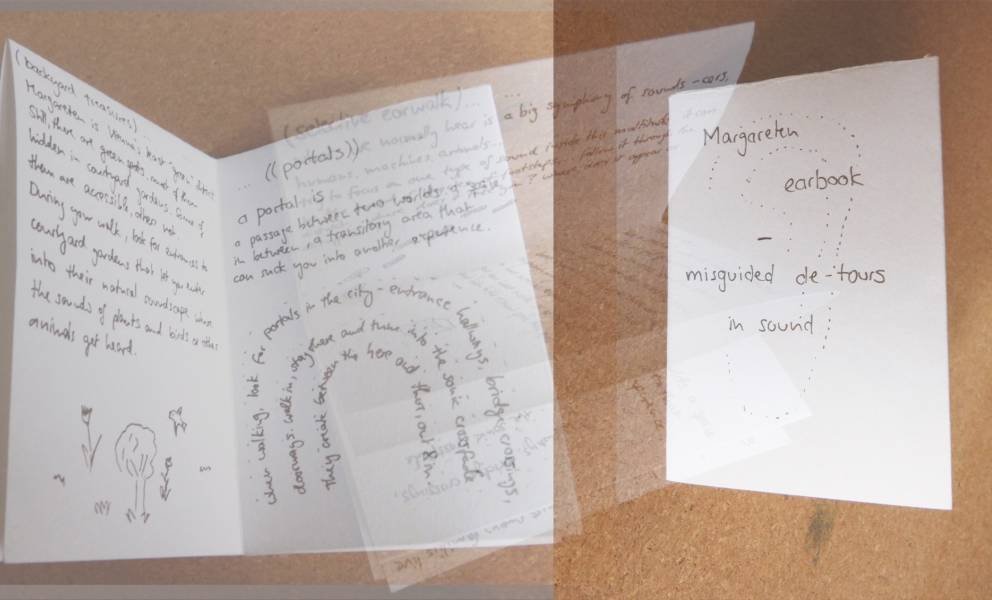

What was described by Hosokawa in the 1980s as strangely deviant social behaviour is now normal, at least in cities, because portable speakers and AirPods are ubiquitous, and every day we encounter people who seem to be present and absent on the bus, on the street or in the park with their ears plugged in, "traveling in their own world". It's no wonder that in recent years, audio walks have become a popular format of sound art, the "Walkman setting" par excellence. I am given instructions, a starting point, have to have an audio device ready, and can then set off on a "tour". Audio walks are balancing acts of attention: I listen to my surroundings at the same time as the audio track involves me in an (imaginary) action. Passers-by, buildings, and situations are transformed into components of a story that I unfold through my listening-while-walking. It's not so easy to create this balance yourself. While the internet is full of tutorials on various media and sound art techniques, from live coding to interaction design, the actual creation of listening experiences, whether in installations or audio walks, is rarely discussed. This is because they are site-specific productions, and staging is - as in theatre - a complex craft. Audio walks are often linear and narrative, similar to audiobooks: there is a core story that is sometimes loosely laid out along the way, sometimes "linked" to the surroundings at individual stations. Station by station, you walk, stop, listen to a story piece by piece, then instructions follow, and you walk, stop again, listen, walk, ... Other audio walks are rather installation soundscapes, the surroundings are painted over and deformed in layers, similar to an impressionist painting.

- How do I design the signpost as part of the overall experience?

- How fast or slow is the pace of events?

- Which external cues can and must I rely on and how can I incorporate fleeting or changing settings, for example in a city on a busy square?

- How do I communicate with my audience - directly or indirectly?

In contrast to sound walks, where the focus is on listening to the environment itself, audio walks invite you to drift between the environment and immersion in a soundtrack. Listening too intensively in a big city can also be dangerous as soon as I have to cross roads. Creating an audio walk is a multi-layered activity between installation work, soundtrack production, directing, and staging. Creating a good, exciting audio walk that engages my audience and draws them into the experience takes a lot of time, exploring locations, research, and testing. And walking, listening, testing, testing, testing. Audio walks as a practice are a lot of work - and are so difficult to document and share, because they only live in and with the place for which they are made. As preliminary stages and experiments, I often think about smaller sound walks and situations at selected locations, which are then put together piece by piece to form larger tours.

But there is not only a trend towards "private" listening in public in sound art: in contrast to audio walks, where the space you walk through merges with the listening experience of the soundtrack and the speakers on your ears are pure mediators, they also come to the fore as physical objects and bodies in sound installations or loudspeaker performances. During the pandemic, when interpersonal contact seemed impossible at times, loudspeakers became companions that could at least give us the closeness of friends, the feeling of being taken care of, in a tangible acoustic way. Locked up at home - with our ears out in the world.

Composers such as Huba de Graaf and Cathy van Eck even take up this moment in their music-theatrical works. They integrate loudspeakers as performers or musical personae (Philip Auslander), thereby blurring the boundaries between the human body and technology. Loudspeakers thus reveal themselves as performative objects that can develop their own theatrical quality not only through their sound but also through their appearance, their materiality, and their position and movements. Part of the fascination with loudspeakers in the theatrical field arises precisely from this interplay between the object, its practical meaning in the respective context, and the sound that is conveyed through it. Playbacks using hidden built-in loudspeakers in theater and music theater contexts are often used to animate situations or objects or to transform them into something other than what is visible. Even if we know that this is a technical sleight of hand, we like to indulge in the illusion that sound brings things to life, gives them a voice of their own, or, as a ghostly presence, indicates the effect of possibly supernatural phenomena. Hearing becomes tangible in loudspeakers as sounding objects, and their design and staging as objects fulfil an old human need for the magic of living things. Hearing thus becomes a transformational act of changing reality that transports the listener into the intermediate realm of reality and imagination.

While headphones create a private and personal sound space in which only one person at a time can immerse themselves, loudspeakers focus on listening as a public, social process. It is no coincidence that in the course of their technical development, loudspeakers were quickly used not only for the purposes of entertainment and art but also for political communication and propaganda because as transmitters they allowed the multiplication, magnification, and dissemination of external messages. Speaking loudly in public means giving the message conveyed more importance. Before the technological age, public speaking needed to be framed by a special context or location, such as the Speaker's Corner in London's Hyde Park, but nowadays any place can become a Speaker's Corner thanks to loudspeakers.

„Wir haben keine Ohrenlider“ (Murray Schafer)

Sound art, especially site-specific sound art that takes place in public spaces, always refers indirectly or directly to the social and political aspects of hearing: who is allowed to sound where and how loudly, who or what is disturbing? Sound installations and interventions in public spaces sometimes generate much more emotional reactions than other art forms because sound intervenes in the public fabric in a very sensitive way. It spreads and is difficult to ignore once made consciously. I can turn away from a visual work of art that I don't like, but not from a sound, because, as the British sound artist Murray Schafer put it, "we don't have earlids". Instead of making us listen away, loudspeakers always, metaphorically speaking, hold up a mirror to us: as transducers of hearing and senses, as devices for hearing-while-transforming, they make us aware of our own hearing in its materiality and fleetingness and make us aware of listening as a balancing act between the acoustic and the visual, between function and magic, environment and our own position.

Margarethe Maierhofer-Lischka

Margarethe Maierhofer-Lischka is musician, researcher and sound artist based in Graz. The focus of her interest is music and sound in its interactions with society, technology and nature. She creates works for radio, theatre and film and enjoys creative and playful explorations of DIY and open source technologies. Also, she is a frequent writer for positionen, freistil and other magazines on experimental music.

Article topics

Article translations are machine translated and proofread.

Artikel von Margarethe Maierhofer-Lischka

Margarethe Maierhofer-Lischka

Margarethe Maierhofer-Lischka