6 Minuten

The journey

As a composer and musician of electronic music since the 1980s, my medium is sound. When I was asked to compose a piece for the Vienna RSO (Radio Symphony Orchestra) in 2009, I had to think about how to communicate with this orchestra. I opted for what I do best – to work directly on sound and listening. Since that year, I have developed two different methods of communication with musicians:

- the live-generated audio score, where the performers have to imitate the live-generated electronic sounds they hear through a loudspeaker

- and the audio score based on acoustic memory, where the musicians are given a set of sound samples to be interpreted on their instruments and for the performance in combination with a synchronized time line score this interpretation is played by memory.

The research journey continues. In a PEEK project at the mdw (University of Music and Performing Arts Vienna), in cooperation with Piotr Majdak (Acoustics Research Institute / Academy of Sciences) and Susanne Kogler (Institute of Musicology / University of Graz), the psychoacoustic and aesthetic characteristics and effects of audio scores of these and other methods are being researched. At the same time, this project will provide a global overview of composers and their different approaches in creating audio scores.

The potential

In electroacoustic and acousmatic music the piece itself is the perfect score stored on a medium and historically not meant to be interpreted by anyone other than the composer her/himself. In the last ten years a new generation of acousmatic music composers started to discover the potential of interpretation. The fact, that now more and more electroacoustic and acousmatic music composers are dead might be one reason, but there is also the desire to shape things in a new way – and this we call interpretation.

As a result, the next step was to also use the medium sound as a score for interpretation by musicians. A new category of compositional technique was born and this field needs to be explored and contemplated.

Audio scores have the potential to convey extremely complex compositional structures directly and can therefore be interpreted by the musicians using simple instructions. This stands in contrast to a visual score, in which musicians have to decode first the visual signs and then translate them into sound. To use this potential we have to take a closer look at “ways of hearing”, to quote Maryanne Amacher, with the instruments of musicological and psychoacoustic analysis and the experiences of composers and musicians.

The methods

a) The live generated audio score

The Virus series

The method of a live generated audio score I developed for the Virus series,starting in 2011 with Virus #1.0 for string quintet. At the beginning there were several major questions: How should a live generated audio score be designed? How should the set up be organized? Who hears what, and why does somebody choose a specific interpretation? Where are my own listening limits? And how is it possible to merge the digital, live generated score with the interpretation of the acoustic instruments?

The electronic resonating sound body is generated live during the performance and is the audio score for the acoustic instruments. It corresponds to the image of a host cell. The acoustic body corresponds to the image of a virus, because the musicians have to attach and adapt to the electronic sound body, they penetrate into it and a synthesis between the two resonating bodies results. The Virus series is an expedition into acoustic perception, a sounding of the responses of our brains in the span of milliseconds, a plea for the precise acoustic moment. It deals with the question “And what do you hear?” This question is dedicated to the audience, the musicians and myself. It implies that every self will experience something different.

Set up:

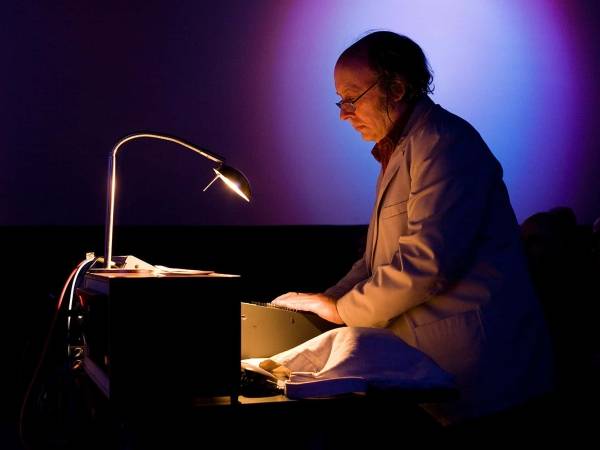

The musicians sit or stand spread out in the space in front of a loudspeaker and try to play what they hear as precisely as possible on their instruments. The electronic sounds – the sound score coming from the loudspeaker – as well as the interpretation by the musicians are audible. The instruments are unplugged, so the speakers project only the sound score. It is important to consider the distances between the musicians, in order to give each participant the possibility to focus on his or her own part within the sound score. A minimum of 3m for instruments with middle or high frequences and a minimum of 5m for instruments with low frequencies is necessary. The composer generates the score live and is therefore a part of the responding system, and together with the musicians she builds a feedback loop. Like the musicians, the composer listens and reacts to what she hears, making decisions in the micro-realm of the score for the further progress of the composition. The audience sits amongst the musicians.

b) The audio score based on acoustic memory

I first used this very different approach in 2017 for the piece Vast Territory. Episode 1 Lily Pond. This first attempt was for 7 minutes only, for strings and wind instruments. The major question was: How does our acoustic memory work. And for how long is this possible without the addition of a written score? In 2018, I composed the music theater piece Pricked and Away working with this method for the ensemble part of the piece.

The musicians follow a sound score played by memory and are thus tied to the oral tradition. Its like telling a story from aural memory. The audio score consists of field recordings lasting 15 to 45 seconds and are given to musicians in advanve for interpretation and memorization. Working with field recordings in audio scores is quite common, but they are usually played to the musicians via headphones for interpretation during the performance. The only approach tied to the oral tradition in contemporary music I know is Eliane Radigue's way of communicating her compositional ideas to musicians, and she even asks these musicians to pass on the piece through oral tradition to another musicians. These other musicians have to refer to the musicians from whom the information is coming. In this way a line of references is created.

Field recordings are a very complex type of sound material, they stimulate the imagination or trigger memories about a specific environment mostly connected with very specific emotions. At the same time field recordings consist of multilayerd sound events and most of the time it's not possible to translate all this acoustic information one to one for interpretation on the acoustic instrument. As human beings we filter this information in an acoustic environment and concentrate on what seems to be relevant for us at a specific moment. A microphone is pritty stupid and will transmit all acoustic information out there. The musician then has to decide which acoustic information is relevant for interpretation, and from musician to musician this can differ quite a lot!

Set up:

Each musician follows his or her very personal interpretation of the sound files regarding to a specific time line score. In a short piece each musician has a stop watch for help to execute the time line. In a long piece the timeline has to be a moving visual score with a cursor to indicate the exact time. The indivitual timeline scores for each musician have to be synchronized. All sounds - the interpretations of the field recordings - are played by memory, the original audio score - the field recordings - is inaudible.

To be continued!

Elisabeth Schimana

Elisabeth Schimana has been working as a composer, performer and radio artist since 1983. She studied Electroacoustic and Experimental Music at the University of Music and Performing Arts in Vienna, Computer Music - Composition at the IEM, Graz and Musicology and Ethnology at the University of Vienna. In her work she has been dealing with space / body / electronics for many years. Elisabeth Schimana gives lectures and composition workshops internationally and founded the IMA Institute for Media Archaeology in 2005.

Article topics

Article translations are machine translated and proofread.

Artikel von Elisabeth Schimana

Elisabeth Schimana

Elisabeth Schimana